Arts

You are here

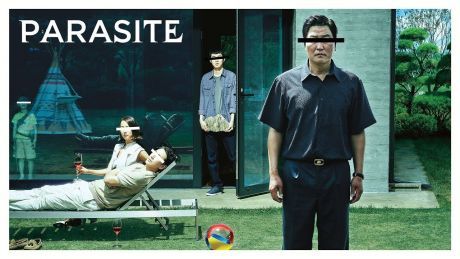

Film review: Parasite (2019) - Crazy Class-conscious Asians

October 26, 2019

Who is this film for? Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite opens with a movie screen-like window where the impoverished Kim family looks out into the street from their semi-submerged dwelling.

They are causally marked as insect-like, feeding off the edges of the formal and informal economies as they collectively assemble pizza boxes, while fumes of insecticide get blown into their home. Their dire financial situation is indicated by the odd, inconveniently placed toilet bowl in the opening scenes.

It’s not the only home with a bizarre architectural feature: the wealthy Park family’s grandly designed house also has a movie screen counterpart, a large and magnificent window that looks out unto a carefully manicured backyard, and they too have their own version of the weirdly placed room.

The reason I ask my opening question is because, while the movie seems to be about class resentment, it may actually be punching down on the less economically stable family. The bourgeois housewife, despite her laughable affectations, is characterized as well-intentioned and naïve. Meanwhile, the husband is shown as a suave, successful businessman. In both instances there is no indication of how parasitical the wealthy are—which contrasts to the parasitical assault of the Kims against the affluent Parks.

The Kims are philistines; they can only appreciate art through googling. If the director is aiming for some type of statement about class, what he comes up with is quite devastating. Instead of class solidarity, the film shows that the lower classes will fight amongst themselves. They will compete and maim with another for the limited resources available to them.

Why can’t they band together and target the actual economic parasites of society? Why is this option not available in the film? Are we to view this film through the submerged window or the grand one?

The financial status of the grifting family is equally quizzical. With their combined incomes, as Mr. Kim remarks, they could move out of their cramped quarters. But they don’t. The only sign of financial improvement is when they dine out at a regular restaurant. So where is the money going?

The financial and class aspects get blurry because the film is ultimately not interested with these issues. It has another allegory in mind: the North and South Korean divide.

As a character remarks, a key edifice was built as a place to hide not just from creditors but also from bombs. The film conflates these two themes, which is why the class aspect becomes less prominent and biting in the second half.

The doubling or repetition of a character’s fate in the film’s final act does not make sense, narratively and visually, if the underlying issues of the de- and re-unification of the Koreas are ignored. The closing sequence stages a deferred and potentially impossible reunion not just among kin but also of these two nations.

Section:

Topics: