Features

You are here

Can violence be moral?

August 6, 2024

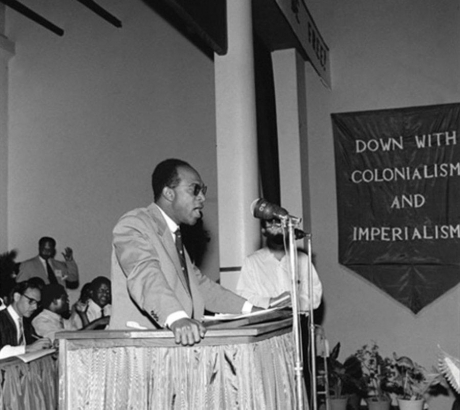

“In all armed struggles, there exists what we might call the point of no return. Almost always it is marked off by a huge and all-inclusive repression which engulfs all sectors of the colonial people.”

These are the words of revolutionary anti-colonial writer Frantz Fanon writing in The Wretched of the Earth in 1961, but it could just as well be about Gaza in 2024.

As a psychiatrist, Fanon believed that the violent struggle of the colonized for liberation was a kind of shock treatment that would “restore confidence to the colonized mind” and “overcome the paralyzing sense of hopelessness induced by colonial subjugation,” but “was only a first step toward the birth of a new humanity.”

Fanon’s treatise on violence has often been misconstrued, by supporters and detractors alike. Fanon does not valorize violence (as some contend), but rather acknowledges that colonialism is a project which is - in and of itself - violence manifested. This violence has shaped the social constitution of the colonial subject. The colonial subject’s land, resources, and life have been seized by a state of violence, and within the framework laid before him, the only route out is violence.

“Colonialism is not a thinking machine,” wrote Fanon. “It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.” The way out of colonial oppression and the colonized person’s “inferiority complex and his despairing attitude,” is through the “cleansing force” of violence. Fanon believed that violent resistance would restore the humanity of the colonized, elevate them psychologically to a position of equality, and deliver social justice: “The native discovers that his life, his breath, his beating heart are the same as those of the settler. He finds out that the a settler’s skin is not of any more value than a native’s skin.”

“The colonized took up arms not only because they were dying of hunger and witnessing the disintegration of their society,” wrote Frantz Fanon in his incendiary book The Wretched of the Earth, “But also because the colonists treated them like animals and considered them brutes. As soon as they are born, it is obvious to them that their cramped world can only be challenged by out and out violence.”

What Fanon implored us to do was to view the struggle of the oppressed as a struggle to create a new mode of being, a new form of humanity. Within the revolutionary struggles of the masses, he insisted, lie the seeds of a new humanity. The ongoing resistance in Palestine today is not a new phenomenon, but is rather the latest episode in a decades’ long struggle for freedom and recognition. This recognition is not the recognition to live within shriveled little cantons and drip-fed subsistence, but recognition as a human being in the holistic sense of the term. The stone throwing, the stabbings, and the bombings, are a reaction to a colonial regime which denies this recognition.

Who was Fanon?

Frantz Fanon was a French physician, psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and author who supported the Algerian struggle for independence from France. Born in 1925 on the Caribbean island of Martinique (which was then a French colony), Fanon left the island at the age of 18 and traveled to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces fighting against Nazi Germany in World War II. After the war, Fanon went to France and studied medicine and psychiatry in Lyon, and qualified as a psychiatrist in 1951.

Fanon became disenchanted with the racism he had encountered in his life and work, and moved to Algeria in 1953. There, he practiced in the native ward where he treated both French colonial officers and Algerian Arab patients. While in Algeria in 1956, Fanon joined the FLN (Front de Libération Nationale - the Algerian Liberation movement) which was actively engaged in an armed struggle against the French.

Algeria by then had been a French colony for almost 200 years, so Fanon’s ideas stem from his knowledge of psychoanalysis and a study of literal colonialism in Algeria.

What makes Fanon’s thoughts and ideas on colonialism and post-colonialism unique and different from others in the field is that Fanon applies his psychoanalyst training at understanding the psychological impact of material causes of colonialism on both the colonizers and the colonized. His most famous works include Black Skin, White Masks (1952), A Dying Colonialism (1959), and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). Frantz Fanon died of leukemia in 1961 at the age of 36, shortly after dictating The Wretched of the Earth (which was published posthumously) to his wife.

“The violence which has ruled over the ordering of the colonial world, which has ceaselessly drummed the rhythm for the destruction of native social forms, that same violence will be claimed and taken over by the native at the moment when, deciding to embody history in his own person, he surges forward into the forbidden quarters.”

We must understand that Fanon was not writing for a white European audience, he was writing for people in the midst of an anti-colonial revolutionary struggle, and so he does not try to hide or dilute his meaning.

Jean-Paul Sartre, in his preface to Frantz Fanon’s work, wrote: “Violence in the colonies does not only have for its aim the keeping of enslaved men at arms length, it seeks to dehumanize them.”

Sartre wrote explicitly of the violence of revolt: “The rebel’s weapon is the proof of his humanity.” On the reaction of the colonial regime to armed resistance, he says: “The colonial army becomes ferocious, the country is marked out, there are mopping up operations, transfers of population, reprisal expeditions, and they massacre women and children. The new man knows this. He considers himself as a potential corpse, that he will be killed. And he accepts this risk, he’s sure of it. Others, not he, will have the fruits of victory.”

This could very well have been a description of Israel’s genocidal actions in Gaza since October 2023, and it’s very hard to read both Fanon and Sartre and not make this connection.

Fanon perceptively diagnosed the disease of colonialism that Israel continues to propagate as it replicates its primary pathology: the obliteration of Palestinians. As a recent UN report states: “Israel’s genocide on the Palestinians in Gaza is an escalatory stage of a long-standing settler colonial process of erasure. For over seven decades this process has suffocated the Palestinian people as a group - demographically, culturally, economically and politically - seeking to displace it and expropriate and control its land and resources.”

Settler-colonialism operates through the elimination of Indigenous people’s existence on the land. Without this reducible element, settler colonialism cannot operate. Settler colonialism is not interested in simply exploiting the “natives”. Rather, it attempts a totality through eradicating its negation, the existence of Indigenous people, and reducing them to an invisible, a persona non grata. This is why the Palestinian-Israeli impasse should not be seen from the angle of a particular event, but rather as a structure that operates on the elimination of Indigenous Palestinians as an entity.

If one examines the history of colonialism (and settler colonialism), there appears to be a consistent pattern: the moral dismissal of non-state perpetrators of violence - via the label “terrorist” (for example: with the Houthis in Yemen, Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and many others throughout history). Perpetrators of violence are always portrayed as acting outside the boundaries of morality, and violence itself is regularly dismissed as irrational or subject to reductive explanations: the assertion of the perpetrators lack of self-control, their dehumanization (as they are usually an or ascribing to them sadistic and psychological tendencies. But is it justified to lump all acts of violence in the same category with resistance movements such as those in Palestine, fighting against foreign occupations that they consider illegitimate? Why are those that are engaged in acts of physical violence deemed “extremists” while those who accept or work with foreign occupying forces deemed “moderates” Who decides, and what is the criteria?

The excerpts below (from The Wretched of the Earth) highlight both the practical and psychological reasons for violence against the colonizer:

“He [the native] (Palestinians in our context) of whom they have never stopped saying that the only language he understands is that of force, decides to give utterance by force. In fact, as always, the settler (Israeli Zionists in our context) has shown him the path he should take if he is to become free.”

At the level of individuals, violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect”

According to Fanon, colonial rule is sustained by violence and repression. With violence as the “natural state” of colonial rule, it follows that in fact it is the colonizers [Israeli Zionists] who only speak and understand the language of violence. As such, only the use of violence by the colonized [Palestinians] can physically restructure society.

Furthermore, Fanon argues that psychologically, violence returns agency to the colonized [Palestinians] who were hitherto dehumanized, and allows them to recreate themselves in a light that is not tainted by the colonizers. In Black Skin, White. Masks, Fanon states that freeing oneself of colonialism through violence can be “cathartic”.

In the context of the Algerians, violence was cathartic as it allowed them to restore the “self” which was systematically destroyed by colonialism. Thus, Fanon theorizes that violence enables the colonized to restructure their country politically, and also recreate themselves and resume a self-determining existence.

Their violence and ours

Fanon emphasized the distinction between the violence of the oppressor and the violence of the oppressed. Moreover, he deepened our understanding of the undeniably emphasized, or “re-cerebralizing”, effect of revolutionary violence. Occasionally, in his political practice, Fanon did elevate armed resistance to the status of the sole “real struggle” that would “radically mutate” the oppressed. Nonetheless, in his last book The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon demonstrates that he was a subtle and complex thinker on how violence could reverse a profound sense of inferiority among the poor and oppressed. He never advocated violence as the prime political instrument.

Fanon understood the deep paradox of the violence of resistance, which is that it is both necessary and, at the very same time, a curse. Suffering from extreme violence and inflicting that violence left both parties, though not moral equivalents, permanently marked. To use Fanon’s language, both were “mutated”. No emancipation - partial, flawed, and uneven as it was after national liberation - could be achieved without the “equalizing” violence of the oppressed. This violence punctured the settlers’ self-image as superior; it asserts, and to some extent reverses, the profound sense of inferiority in the colonial subject. Interestingly, Fanon was clear that after independence, those colonizing “jackals” who had inflicted the worst violence of the colonial state, and those who had suffered this violence would only be redeemed by psychiatry.

Without denying the potential of violence to be moral or immoral, understanding Fanon’s thoughts on violence as both a creative and cathartic, yet limiting, power for the colonized, allows us to look at other revolutionary movements, whether anti-colonial or anti-establishment, as surges or collective movements acting against perceived aggressors, rather than in conformity with universal moral norms.

The struggle in Algeria ended with the defeat of France and the independence of Algeria. We are at a point of no return for Israel and its Western backers. Palestinians are at the mercy of the world’s most powerful military machine armed by the United States, with only Hezbollah in Lebanon, Iraqi militias and the Yemeni Houthis backing them with a blockade of the Red Sea and strikes on US and Israeli forces. But politically, in the global South and among the public in the West, the cause of Palestine has never been stronger, and the West’s position never so unpopular.

Section: