Reports

You are here

Quebec, racism, and the left

May 20, 2021

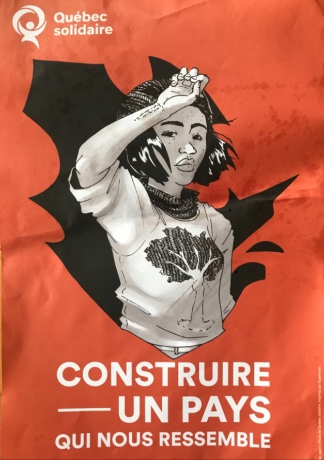

This month marks 15 years since the founding of Québec solidaire (QS), a party far to the left of the NDP in of English Canada.

QS has transformed the political landscape in Quebec. It has provided a left alternative to the Quebec corporate elite to voters, both to an older generation who came to view the Parti québécois (PQ) as bankrupt, and to a younger generation who didn’t see anything worth voting for. At its founding in 2006, QS embraced the goal of being “a party of the ballot box and a party of the street,” to give a voice to the movements in the Quebec National Assembly.

But on this anniversary, QS is embroiled in a destructive internal debate. This debate has revealed very real tensions about how this relatively new party fails to confront systemic racism both internally and externally, and the pressures of electoral politics on questions of principle.

In 2018, the party was able to elect 10 candidates to the Assembly – and then had to contend immediately with the election of the right-wing CAQ, even with a minority of the popular vote. The CAQ knew right away what it had to do: play the racist card that right-wing populist governments around the world have played to prey on despair.

The internal debate within QS eclipses the real debate over how QS should be challenging systemic racism in Quebec society as an electoral and activist party.

What happened?

In April in the lead-up to a national council meeting of 200 members, the party leadership put forward a motion to censure an internal anti-racism collective of QS members, the Collectif antiraciste décolonial (CAD).

A number of accusations were levelled at the CAD by the leadership, but the trigger for the censure motion was when the group uncritically posted comments made by University of Ottawa professor Amir Attaran that referred to the Quebec government as white supremacist and to Quebec itself as “Alabama of the North,” referring to the killing of Joyce Echaquan in a Quebec hospital.

The leadership’s motion of censure was introduced with little warning to the membership, with discussion confined to social media and a very short virtual debate. At the QS national council on May 15, members voted to support the leadership’s motion for censure. They also voted in favour of potential dissolution of the collective. An amendment to refer the motion to mediation failed.

The leadership’s motion of censure was wrong, as was the members’ decision to support it. But it is part of a bigger picture beyond QS.

This article will attempt to explain the forces at work. But the bottom line is that QS, like any political formation, is not exempt from systemic racism and the way it is being instrumentalized by the populist right to great effect to divide the forces of the left. This is by no means unique to Quebec, and by no means is the left outside of Quebec living up to the challenge either.

Is Quebec more racist?

This sad development will no doubt further fuel the argument now prevalent and accepted as “common sense” that the people of Quebec are more racist than anyone else in English Canada. The internal QS battle made the mainstream press in Quebec. Even if it hasn’t to the same extent in English Canada, it needs to be understood. It is part of the common struggle the left has to contend with when it comes to questions of racism and imperialism.

The NDP has had its own very public battles over its position on the question of Palestine. So, the news of this dispute in Quebec should not be met with any self-satisfied attitude that somehow sees these political failings as stopping at the Quebec border.

That said, the fierce attempt in mainstream Quebec politics to direct Quebecois identity towards an identitarian and ultimately racist nationalism pursued by all other political parties in Quebec has had an impact on the political landscape, and on QS as well. How could it not, given that QS has entered as a contender in a political arena fundamentally hostile to its member-driven political principles of social justice?

Double-standard

The heavy-handed response of the leadership betrays a serious double-standard within the party on the question of systemic racism. One of the most glaring examples of this is the earlier failure to have censured another collective within QS, the Laïcité (“secularism”) collective, which had been circulating Islamophobic material for a while before it was finally banned from the party in September 2020. It was given a year’s notice (already well overdue) and opportunity within internal party procedure to explain itself – as opposed to the three weeks the CAD was given.

But an even more glaring example of the double-standard were the comments made by elected deputy Émilise Lessard-Therrien of Rouyn-Noranda-Temiscamingue about real estate speculation in rural areas in 2019. She clearly singled out Asian speculators as ‘roaming’ in her constituency. Not only was this inaccurate in terms of the real threat in her region, which comes from domestic real estate speculation, it clearly fed anti-Asian racism. And though it was debated within the party membership, it was never condemned by the party leadership in any way.

At every turn until now, the membership has questioned this double standard, even when it pitted them against the leadership. In fact, the membership voted by more than 90% in support of a position rejecting all bans on religious symbols in any profession. Unfortunately, this was only after the ruling CAQ government introduced such a ban, Law 21, the day after they were elected. And this QS vote happened after the parliamentary breakthrough - and despite opposition of some on the leadership, who supported a watered-down version of Law 21. The membership came through, despite the confusion that had reigned for years in QS on the question of so-called secularism.

But this ability of the membership to repeatedly be the conscience of the party did not come through this time. Why not? Is it the pressure of looking good for elections, and the way the leadership was able to promote its position in that context, at a meeting that was to chart a path towards the Quebec elections of 2022?

How did this happen?

Presse-toi à gauche, a publication that gives voice to some left members of QS, interviewed a founding member of QS, and also member of the CAD, Sibel Ataoğul, about her experience of the double standard and the way process was misused within the party. In it, she gives the following reason why this may have happened:

“We (QS) seem to have achieved everything possible in Montreal for the moment, and we’re betting that this question of anti-racism is not that popular outside of Montreal. This is why this motion against the CAD seems to me to be a political battle.”

If this is indeed what the leadership of QS is betting on, it is scandalous. But this is not necessarily true for how the membership understands it. And it is the opposite of what a bold party of the left should be betting on.

QS should not just be focused on ‘winning’ votes and then sitting on them. It needs to win hearts and minds to a project that counters the other side, in the long term – for the principles of social justice, and not about branding for elections – or reacting to the racist corporate media.

But why then wasn’t the membership of QS able to be a better corrective to this, at least in the CAD debate, as it has in the past? Some of it might have been the impact of the leadership’s version of what happened with the CAD, and the ambush of the motion. It might also be the collapse in member engagement when the leadership and parliamentary wing of QS essentially shut down the party in the interests of public health at the start of the pandemic. The party bled active membership as a result of not meeting at all for months, even virtually.

In an interview with Socialist Worker/socialist.ca following the censure, Sibel Ataoğul noted three things that explain what happened: systemic racism, electoralism, and the bureaucratization and professionalization of QS.

As Sibel said, systemic racism is ongoing: the party reproduces internally the struggle that BIPOC people live outside the party every day. But this specific fight blew up when and how it did because of the pull of elections: "purely because the party is changing focus from pulling debate to the left to gaining power." The leadership felt the comments around Attaran could hurt them in the upcoming elections and took swift action to distance themselves.

But because it had to be swift, the leadership's motion was a "sucker-punch." For Sibel, this also explains why this vote was so different from the QS vote on Law 21: "then we had time to convince members, and the leadership didn't want to see the same thing happen with this vote." Despite the short time in the lead-up to the vote, she participated in a number of Zoom meetings and won them over, but this reality on the ground was not reflected in the vote: "if it hadn't been a sucker-punch, I truly think they (the leadership) would have lost the vote."

The third issue is the growth of a party "machine," with a move from militant and activist work to paid labour and concern by both members of the assembly and party staff about keeping their jobs. This is the structural threat the party is facing, a problem that is pushing it to become more like the NDP. The “party of the ballot box” and the “party of the street” are confronting each other.

What brought QS to this point?

QS became what it is today principally because of two breakthroughs in movements on the ground: the massive grassroots anti-globalization movement within Quebec against the Free Trade Area of the Americas in April 2001, and a victorious student rebellion in 2012 that toppled a government. Both these movements helped fuel a massive movement for climate justice that put the largest numbers per capita in the world on the streets of Montreal in the climate strike of September 2019. On top of this, in 2003, the massive anti-war movement in Quebec that kept Canada out of the war in Iraq helped increase the political space for a party to the left of the PQ.

This spring we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Quebec City protest at the Summit of the Americas. This was part of an international movement and drew up to 80,000 through deep local organizing in Quebec City itself, and right across Québec. Out of this protest came the first electoral breakthrough of the Union des forces progressistes (UFP) which came to co-found QS along with Option citoyenne.

This spring also marks the 49th anniversary of the 1972 Common Front general strike that led to the take-over of nine towns by workers and produced an anti-capitalist manifesto that declared international solidarity for workers’ rights. It was, at the time, the largest general strike in North America. But a few short years later, the PQ was able to take hold of the aspirations of that movement and channel it in a much narrower direction to elections, a failed referendum on independence and neoliberal austerity policies.

QS was a bold attempt to break the stranglehold the PQ held on the left since that time. In the 2012 election, after the magnificent student strike, the PQ introduced a racist “Values Charter,” more oil exploration and a budget that targeted the poor. This sealed their fate.

In the interim, Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, the largely recognized leader of that student movement, threw his lot in with QS, and the party grew enormously and dropped in average age overnight.

But QS is also shaped by the society in which it was born. A tide of racism has poisoned politics in Quebec in fundamental ways, most obviously in support of Law 21, a ban on religious symbols that has Islamophobic implications. But also, popular discourse in Quebec has made the question of whether systemic racism even exists in Quebec a debate, even on the left. The objection is that to even raise the question amounts to Quebec bashing.

The long history of this is that Quebec is the remnant of a colonizer, New France, that itself became colonized – and since its Quiet Revolution, an elite within Quebec has become incorporated into Canadian capitalism. It has narrowed the broad movement for social change that fueled the Quiet Revolution to a fight over language, as the CAQ is doing now. But in the 60s into the 80s, the movement for French language rights within Quebec were crucial fights for fundamental equity for the Quebecois people who were denied work and education in their own language. And yet back then, in the debates over Bill 101 (the French language charter), the demand for that basic right was unjustly met with accusations of racism from English Canada.

The short history is that right-wing parties like the CAQ have capitalized on this past to do what most right populist parties have done: find an issue to divide the left. And so, they have campaigned to equate any discussion of systemic racism in Quebec today with Quebec bashing.

What is the way out?

The story within QS is not over yet. It is possible that the membership could fight for the future of its party and challenge the ceding of ground to systemic racism within its own structures and to the electoral pressures from the outside. The reality of systemic racism – in Quebec as elsewhere – continuously produces movements of resistance. The activist base of QS is affected by this resistance and has given it expression in the past – most notably in its rejection of Law 21. As with the ‘rest of Canada’, struggle on the ground will shape what happens within left political parties.

While activists in QS debate the way forward, a mass movement of solidarity with Palestine has erupted around the world. Across Turtle Island, this movement has been influenced by the movement for Black Lives and struggles for Indigenous sovereignty. Building the forces of these struggles is the key to challenging racism and strengthening the forces of the left.

Section: