Features

You are here

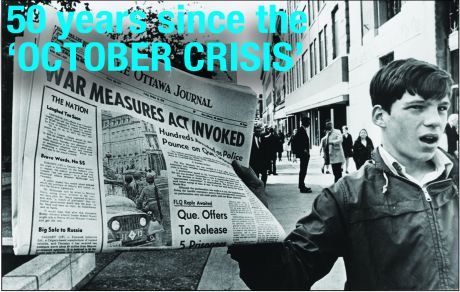

Fifty years since the “October Crisis”: a not-so-quiet Revolution

October 5, 2020

The events of October 1970 are infamous in both English Canada and Quebec for completely different reasons. How should socialists remember the story today?

With the exception of the CBC podcast Recall, which produced a series called “How to Start a Revolution,” mainstream media in English Canada would prefer to ignore it – unless it can reduce it to nothing more than an act of terror. But socialists should not make this mistake, especially in English Canada.

To start, here is a pop quiz. Was the 1970 October Crisis:

- The kidnapping of a British diplomat and the Deputy Premier of Quebec by the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ)

- Part of a world-wide movement of colonized people claiming independence and challenging political norms of imperialism and capitalism

- An act of class struggle by a francophone minority, which at the time in Quebec and in the Canadian state was mostly working class and marginalized

- A pretext for the Canadian state to crack down not only on the FLQ but on all progressives and dissidents in Quebec

- A suppression of civil liberties and freedom of the press for everyone in the Canadian state when the War Measures Act was imposed

- All of the above

If you guessed “all of the above” you are correct. But a good student of revolutionary history explains their answers.

The “terror” narrative

This is the standard telling of the whole story of the October Crisis: the kidnapping of British diplomat James Cross and Quebec Minister Pierre Laporte. Acts of violence against members of the ruling class, and small-scale bombings that could have injured ordinary people, and sometimes did, is central to the story, but not the whole story. Physical violence was only one part of the Quebec liberation movement that had emerged in the 60s and continued throughout the 70s – and was highly debated as a tactic.

Also, this strategic debate over violence and non-violence was raging at the time in liberation movements around the world, frustrated by the limits of “democratic” means of making progress, and searching for an effective way to achieve results. By 1970 this debate had already found expression in the US Civil Rights movement in the evolution of Martin Luther King’s thought and the different tactics embraced by Malcolm X and the Black Panthers.

One of the results of the FLQ kidnapping was to force the CBC to read the FLQ Manifesto over the air on television. This was an attempt to reach a wider layer of people and put out a call for collective action against both Quebec oppression and capitalism. The FLQ tactics themselves may not have been effective in mobilizing masses of people to take action, but the reasons behind them were, and the Manifesto planted a seed that grew in different ways. Several members and supporters of the FLQ later changed tactics for ones that favoured mass mobilization over individual acts: the question wasn’t primarily about violence but about the best way to build a movement.

The kidnapping also provoked the War Measures Act, which laid bare the naked repression the Canadian state is capable of, and which fuelled anger in the years to come. To this day it stands as a reminder of who the real perpetrators of violence are.

One of the acts of so-called “terror” the FLQ was planning earlier, in 1963, was to blow up the statue of Sir John A MacDonald in Montreal – the very one that was pulled down in a BLM protest in 2020. Though it was by different hands, Sir John A finally got the end he deserved.

Internationalism

The FLQ and the wider Quebec liberation movement were deeply influenced by national liberation movements in the global south, notably by the writings of Frantz Fanon, but also by active struggles against colonialism. Like all of these movements on the left of national liberation struggles, the FLQ and those they inspired had to figure out the relationship between liberation from the external constraints on their national development and the differing class interests within their nation.

This was a source of disappointment, confusion, and sometimes repression for many left movements within anti-colonial struggles throughout the global south in the 50s and 60s, sometimes just at the moment of achieving national liberation. There was always a class within the new nation prepared to steer anti-colonial victory towards the economic interests of a wealthy and powerful minority.

This was one of the things the founders of the FLQ stood against. Their view of Quebec liberation was anti-capitalist and they spelled it out in the Manifesto that was read out to all on the CBC:

“Production workers, miners, foresters, teachers, students, and unemployed workers, take what belong to you, your jobs, your right to decide, and your liberty. And you, workers of General Electric, it's you who makes your factories run, only you are capable of production; without you General Electric is nothing!

Workers of Québec, start today to take back what is yours; take for yourselves what belongs to you. Only you know your factories, your machines, your hotels, your universities, your unions. Don't wait for an organizational miracle.

Make your own revolution in your areas, in your places of work. And if you don't do it yourselves, other usurpers, technocrats and so on will replace the handful of cigar smokers we now know, and everything will be the same again. Only you are able to build a free society.”

Geoff Turner, maker of the CBC Recall podcast series on the October Crisis, told the CBC that this connection with the international debates of the time was central to the story he wanted to tell: “I want people to see that the FLQ was part of something bigger that was happening in the world in that moment. All over the world people were rising up against colonialism and oppression, and the FLQ saw themselves as part of that. They had direct links with groups like the Weather Underground and the Black Panthers. There are some really fascinating stories in those connections.”

While parts of the podcast suffer from the tendency to fall too easily into the “terror” side of the story, Chapter 4, “The Whole Wide World,” is filled with clues about how to understand the international dimension of the FLQ crisis at a time when “revolution was in the air.” It begins with a quote from Ed Sullivan’s visit to Cuba just before the US government started vilifying the Cuban revolution: Sullivan says hopefully this will be a source of inspiration for the US to come up with the sort of democracy they should have too.

Turner also admits that he had always thought of the FLQ as a separatist movement, but “when you learn what they actually wrote and said, it becomes clear that their primary goal was to instigate a socialist revolution. They imagined a more just, equal society, and language and sovereignty were part of that, but really it was about class struggle.”

Nation and class

The FLQ Manifesto is as fundamentally about a fight against the rich as against Quebec oppression and sees the two as intertwined. Think about how this sounded when read out live on TV in 1970, by a very uncomfortable CBC presenter:

“We have had our fill of promises of jobs and prosperity while we always remain the cowering servants and boot-lickers of the big shots who live in Westmount, Town of Mount Royal, Hampstead, and Outremont; all the fortresses of high finance on St James and Wall streets, while we, the Québecois, have not used all our means, including arms and dynamite, to rid ourselves of these economic and political bosses who are prepared to use every sort of sordid tactic to better screw us.”

At the time the Francophone capitalist class within Quebec hardly existed, but the FLQ did call out the rising technocratic class that would soon form their ranks in business by including Outremont, an enclave of the Francophone elite, in the list of neighbourhoods and companies guilty of robbing and subjugating the working poor of Quebec.

The reality at the time was that being a Francophone largely meant you were not only working class but relegated to the lowest-paid jobs (even less paid for the same jobs as anglophones in Quebec), least-educated, and not able to access services and rights in your own language. Something the few upper-class francophones - notably Pierre Trudeau, who attended the most prestigious schools available to a francophone in Quebec - did not suffer from in the least. Nevertheless, at the time, the connection between national oppression, language, and class was stark.

But the Manifesto didn’t just describe the evils of capitalism, it gave its victims in Quebec a human face, in prose that invited not only sympathy but solidarity and a sense of dignity for those who needed to feel the confidence to fight for themselves:

“The brave workers for Vickers and Davie Ship, who were thrown out and not given a reason, know these reasons. And the Murdochville men, who were attacked for the simple and sole reason that they wanted to organize a union and who were forced to pay $2 million by the dirty judges simply because they tried to exercise this basic right - they know justice and they know the reasons.

Yes, there are reasons why you, Mr Lachance of St Marguerite Street, must go and drown your sorrows in a bottle of that dog's beer, Molson. And you, Lachance's son, with your marijuana cigarettes ...

Yes, there are reasons why you, the welfare recipients, are kept from generation to generation on social welfare. Yes, there are all sorts of reasons, and the Domtar workers in East Angus and Windsor know them well. And the workers at Squibb and Ayers, and the men at the Liquor Board and those at Seven-Up and Victoria Precision, and the blue collar workers in Laval and Montreal and the Lapalme boys know those reasons well.”

And think about how the following part of the Manifesto resonated across people’s living rooms, pointing a finger at where the real terror comes from:

“And the Montreal policemen, those strongarms of the system, should understand these reasons - they should have been able to see we live in a terrorized society because, without their force, without their violence, nothing could work on October 7.”

It was only 18 short months later, in May of 1972, that the full force of the call to class struggle was taken up. Not for more kidnappings or bombings or any more individual acts, but to use the strongest weapon that any oppressed people has: the power to shut down the system by withdrawing their labour.

Throughout Quebec, May 1972 saw the largest political, “illegal”, general strike in North American history, only bested at that time by the general strike in France exactly 4 years earlier (at that time the largest strike in the world). In Quebec, the strike resulted in the temporary takeover of 9 towns, including radio stations, which they used to broadcast messages and music that were not only about Quebec liberation but anti-capitalism.

The Quebec union federation central to this mass strike, the CSN, put out their own manifesto in 1972. And like the FLQ Manifesto, it targeted capitalism as much as Quebec oppression for why Quebec workers needed to resist, in ways that even surpassed the FLQ Manifesto.

In a gesture of solidarity largely unknown in English Canada today, the 1972 CSN Manifesto also called for the liberation of English Canada from the oppression of US capitalism – an understanding that much of the English Canadian left had of Canada’s situation at the time. Leaving aside the debate over Canada’s alleged “oppression” by the US, the fact that Quebec unions extended solidarity to the people of the state oppressing them, against what was perceived as a greater enemy, is untold history emanating from this extraordinary time.

The crack down

Another piece of little-told history in English Canada is the wide net the RCMP brought down on thousands in Quebec – because it doesn’t fit the “terror” narrative (the FLQ numbered a few hundred at best).

The fact that the War Measures Act was used not just to target the FLQ but anyone remotely connected with the Quebec cause - and really anyone involved in progressive movements - was surprisingly covered in the English media on the thirtieth anniversary of the Crisis. The article was titled “October Crisis hit unknowns the hardest: majority detained by War Measures Act were street activists, students, intellectuals” (Globe and Mail, October 16, 2000, by Ingrid Peritz).

The article puts a human face on the moment: Nicolas Galipeau, who at the age of 15 was pulled out of his home during dinner and jailed and interrogated under the provisions of the War Measures Act, because he had the “wrong parents.” His mother was the celebrated Quebec nationalist singer of the 70s, Pauline Julien, and his stepfather was poet and journalist Gerald Godin, also a well-known nationalist, and both had themselves been arrested and detained hours after the Act came into effect. The police came for their children a week later. The officers explained that civil liberties had been suspended and the police were free to raid the house without a warrant.

The War Measures Act let the dogs off the leash. Two years later, in October 1972, the RCMP engineered a fake arson to create a pretext to clamp down on sympathisers of the Parti Quebecois, which had been founded 4 years earlier. Keep in mind that this was after the massive general strike of May that year.

The RCMP burned down a barn they identified as owned by relatives of FLQ members connected to the kidnapping - and that they believed was to be used as a meeting place for Quebec separatists with members of the Black Panthers. But as VICE News reported in a 2017 article titled “The story of how the Canadian police committed arson to stop a Black Panther meeting”: “The RCMP, which had been caught unprepared by the October Crisis, faced pressure from their political bosses to step up surveillance and disruption of radical elements in Quebec…In the years that followed the October Crisis, an officer with the security division of the RCMP would work with Quebec and Montreal police to do whatever it took, in their eyes, to stop the threat of radical separatists.”

This incident was part of the “Royal Commission of Inquiry into Certain Activities of the RCMP.” But there is a much better account in the excellent film “Les Ordres”, in French with English subtitles (a review of the film will appear as part of this series here soon).

It was the actions of elected officials of the Canadian state in enacting the War Measures Act that gave confidence to the RCMP to take the law into their own hands. Though what they did was eventually uncovered and determined as illegal, it was only through investigative digging and pressure by those who tried to hold them accountable.

Civil liberties

The War Measures Act, though not enacted since October 1970, is still in effect in the Canadian state, though its name has changed to the “Emergencies Act.” We should be under no illusion that its sweeping powers could not be enacted again against any segment of the population that dares to stand up to established power.

Its name was invoked at the start of the COVID crisis and at first Trudeau Junior did not exclude that possibility - again, a threat to use it against ordinary people not to protect them, but to reinforce how the state thinks it should handle the pandemic. The policing of pandemic rules that did occur predictably targeted racialized people primarily.

We must remember the words of Trudeau Senior when asked by an anglophone journalist how far he was willing to go with the War Measures Act in October 1970:

Trudeau: Yes, well there are a lot of bleeding hearts around who just don't like to see people with helmets and guns. All I can say is, go on and bleed, but it is more important to keep law and order in this society than to be worried about weak-kneed people who don't like the looks of a soldier's helmet.

Ralfe: At any cost? How far would you go with that? How far would you extend that?

Trudeau: Well, just watch me.

Ralfe: At reducing civil liberties? To that extent?

Trudeau: To what extent?

Ralfe: Well, if you extend this and you say, ok, you're going to do anything to protect them, does this include wire-tapping, reducing other civil liberties in some way?

Trudeau: Yes, I think the society must take every means at its disposal to defend itself against the emergence of a parallel power which defies the elected power in this country and I think that goes to any distance. So long as there is a power in here which is challenging the elected representatives of the people I think that power must be stopped and I think it's only, I repeat, weak-kneed bleeding hearts who are afraid to take these measures.

The journalist, Tim Ralfe, also challenged Trudeau on the way freedom of the press was being treated for questioning the use of martial law. While the TV reading of the FLQ Manifesto had been a demand of the kidnappers, many other media sources, including English ones, printed it voluntarily – including the University of Toronto student newspaper, the Varsity.

On the 40th anniversary of the crisis, torontoist.com published the following: “Over the month that the War Measures Act remained in effect, most incidents related to it in Toronto were either debates or problems with the printing and distribution of publications that included FLQ manifestos, as the Varsity discovered in early November. When the paper’s printer refused to touch one offending article, the editors replaced it with a photo of a gagged man with ‘censored’ written across the tape, captioned ‘guess what folks’.”

Quebec today

The question of self-determination for Quebec today exists in a different context from October 1970. The Quiet Revolution achieved a crucial victory on the question of language rights but left fundamental social questions unresolved.

The years since the early seventies saw the growth of a well-entrenched Quebec ruling class, which only views its future as part of “Quebec Inc,” Francophone capitalism that can either coexist within the federal structure or marginally push against it to achieve some national control - most of which only serves to protects elite interests or actively works against the real interests of ordinary people in Quebec.

Most tragically, the internationalism that characterized the emergence of the Quebec liberation movement throughout the 70s has now been replaced in Quebec mainstream politics by an identitarian nationalism that not only removes all the social justice and anti-capitalist aspirations from the fight against Quebec oppression, but also opens the door to the open racism and Islamophobia that is spreading throughout the global North.

There is no connection between the politics of the FLQ and any of the other mainstream parties in Quebec today: not the PQ, which abandoned long ago its connection to this socially-progressive history, not the Quebec Liberals, who are really just the inheritors of the Trudeau legacy, and certainly not the social violence of the current right-wing government of Quebec, the CAQ, its imposition of Law 21 against religious symbols. All of these parties have long embraced neoliberalism and austerity and rejected any notion that Quebec liberation has anything to do with broader social liberation.

The only electoral party that has tried to swim against this stream is Quebec solidaire. It is trying to reassert that any vision of Quebec independence must be linked to a vision of social justice. But for this vision to succeed in Quebec, it must be won well beyond the ballot box, through movements of resistance and struggle that can bring Quebec liberation back to its anti-capitalist and internationalist roots. As the FLQ Manifesto declared, “We want to replace this society with a free society… by a society open to the world.”

Those roots are still remembered by some with a close connection to this history, who have tried to pass it down, and it will be interesting to see how that remembrance and discussion takes place in Quebec in the coming month. But that would be the subject of another article. This one is about how those outside Quebec should reflect.

Canada today

This is also the 50th anniversary of the enactment of martial law, a Canadian law that can be used again – in the words of Trudeau Senior: “against the emergence of a parallel power which defies the elected power in this country.”

This is also why English Canadians should mark 50 years since: to say never again.

The power to enact state repression against tactics employed against injustice, tactics that can ultimately always be labelled as “terror,” “violence” and “insurrection” as defined by those who rule unjustly, is a power that must be opposed. The power to do so lies with us, just as the authors of the FLQ Manifesto believed.

The next target could be challenges by Indigenous struggles to the Canadian state, like the rail blockades in solidarity with the Wetsu’eten. What stayed the hand of Trudeau Junior against them, for awhile, was the militancy within Indigenous communities but also the widespread support beyond.

Thousands of settler sympathisers did not buy into the vilification of the blockades because, in the words of the FLQ Manifesto: “they know justice and they know the reasons.”

Section: