Features

You are here

Preventing climate chaos: ideas that can win

July 30, 2019

I write this in the aftermath of another European heatwave. Across the continent, weather records tumbled as millions sweated in extreme temperatures. Parisians endured 42.6 degrees Celsius, breaking a 70-year-old record. It was only one of many examples. Five days of heat was followed by heavy rain and storms. In Barcelona, Spain in just 30 minutes 47 litres of water was dumped per square metre.

These weather events have already led to several deaths, though we don’t know the full extent. But we know that extreme weather always has a disproportionate impact on the poor, women and people of colour. In 2003 a longer European heatwave led to 35,000 deaths. In that year almost 15,000 French citizens died, mostly elderly and poor, who could not afford air-conditioning or lived in inadequate housing.

Globally the environmental crisis means that this experience is magnified, encompassing tens of millions. In 2015, 192.3 million from 113 countries where displaced as a result of “natural disasters”. Again this is exacerbated by class, sex and race under capitalism. Women and children are, according to the UN, fourteen times more likely to be the victims of an environmental disaster. Black and Asian communities are more likely to be in areas vulnerable to events like floods.

They are also the least likely to receive justice in the aftermath. Eleven years after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005 one in three Black residents had returned home, despite living in the world’s wealthiest economy. Back then, veteran Civil Rights campaigner Al Sharpton, argued against media use of the word refugee to describe victims, “They are not refugees wandering somewhere looking for charity. They are victims of neglect and a situation they should never have been put in in the first place.”

Sharpton’s insightful comment contrasts with those who see the current weather extremes as one-offs. In the UK the BBC celebrated falling temperature records with barely a mention of climate change. We should understand these events as alarm bells whose clamour is warning us of the need for urgent action. How else to understand the “unprecedented” 100 Arctic wildfires of the “worst ever season”?

These are not random weather events. Nor are such disasters natural. They are the consequence of economic and political decisions made in the interest of capitalism.

So it is heartening to see the emergence of new, radical environmental movements. In 2018 the magnificent school strikes began, inspired by Greta Thunberg. In the UK, and now spreading globally, we have also seen the emergence of Extinction Rebellion. Thousands of people have taken part in mass civil disobedience. The determination of the protesters demonstrated by the numbers prepared to be arrested – thousands at a time – to clog up the justice system. For those of us who’ve been environmental activists for some time XR is a breath of radical fresh air. The meetings are often huge – in my hometown of Manchester we regularly get 100 to 200 people at XR’s weekly gatherings.

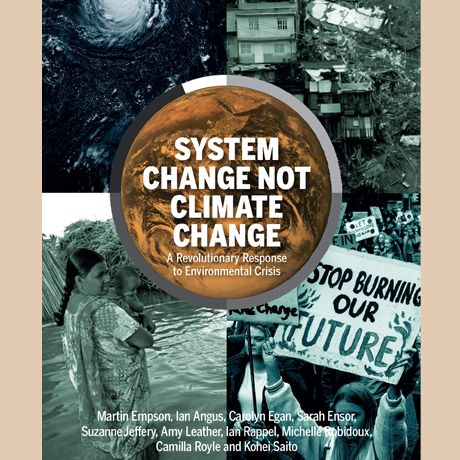

The debates at these meetings, on the climate strikes and in numerous meetings taking place to plan September’s climate strikes are widespread. But one key question keeps arising, though it often takes different forms: “Can capitalism solve the environmental crisis, and if not, what sort of system do we need?” It’s epitomised by the slogan “System Change not Climate Change” which seems to appear, almost by magic, on every environmental protest around the world!

It’s for this reason that we published our new book “System Change not Climate Change: A Revolutionary Response to Environmental Crisis”. We want this to be a tool to understand why it is that capitalism is so destructive to the environment and how this manifests itself. In it, activists from across the world explore crucial debates for the movement. Their chapters look at how capitalism developed as a fossil fuel system, and why almost every aspect of it – from its reliance on plastic to industrial agriculture – is devastating for the planet.

The book doesn’t shy away from theoretical questions, though it tries to make these as accessible as possible. Canadian socialist Ian Angus looks at how Karl Marx and Frederick Engels developed the idea of “metabolic rift” to explain the way capitalism breaks the link between human society and nature. Japanese Marxist Kohei Saito explains some of the ideas in his award winning book “Karl Marx’s eco-socialism” to show how seriously Marx took ecological ideas.

I am particularly pleased that two other Canadian activists, Carolyn Egan and Michelle Robidoux, have written on the movements against the tar sands for the book. They highlight the way that Indigenous First Nations people have been central to united movements involving workers and environmentalists to both stop fossil fuel developments and fight for alternatives. This is a story that is not well known in Europe and we’re pleased to have the opportunity of bringing it to a wider audience.

One of the frightening consequences of capitalism’s environmental crisis is the Sixth Extinction. Two chapters look at this – one highlighting how agriculture helps drive the biodiversity crisis. The other explores how capitalism’s solutions are based on fantasy projects that use the same financial tools that have caused the problem in the first place. “Natural capital” is supposed to save the planet by putting a price on nature, but it only leads to further drives to accumulate wealth. Despite the dreams of entrepreneurs hoping to make profits from “green capitalism” the treadmill of capitalist production only further destroys as wealth is accumulated for the minority.

Preventing climate chaos becoming a runaway disaster needs mass movements involving workers, environmentalists and Indigenous communities. In this struggle socialist ideas have a central place, firstly because they help us to understand the system and why it behaves like it does. But also because socialism offers a vision of a different way of organising society – a world where production is in the interests of people and our environment. Such an economy is not a top-down system, but one based on the democratic planning of production, with the mass participation of millions of people. The old slogan, "The workers have nothing to lose but their chains, they have a world to win" has never been so pertinent.

Martin Empson is a British socialist, climate campaigner and co-author/editor of System Change not Climate Change. To order, contact Bookmarks

Section: