Features

You are here

The radical history of oil workers

June 16, 2017

Oil workers embody the contradictions of capitalism. Their labour extracts from the earth fossil fuels that are the life-blood of the system—generating massive profits for oil companies and power for the states that back them. But this work extracts a health toll from workers and surrounding communities, and contaminates the environment. When oil workers have moved into action to challenge these contradictions, they have helped topple regimes, win health and environmental regulations, and imagine a world beyond capitalism and oil.

Capitalism and oil

Two hundred years ago the economy was based on water power, but Britain’s industrial revolution changed it to coal-powered steam. As Andrea Malm explains in Fossil Capital: the Rise Of Steam Power And The Roots Of Global Warming, “The transition from water to steam in the British cotton industry did not occur because water was scarce, more expensive or less technologically potent – to the contrary, steam gained supremacy in spite of water being abundant, cheaper and at least as powerful, even and efficient.”

As a writer explained in 1833, “the invention of the steam-engine has relieved us from the necessity of building factories in inconvenient situation merely for the sake of a waterfall. It has allowed them to be placed in the centre of a population trained to industrious habits.”

In other words the fossil fuel economy emerged—first with coal and then with oil—because capitalists wanted a mobile source of power disconnected from the earth and a more exploitable pool of human labour. Capitalism’s privatization of the commons, driving people off the land and into cities to produce commodities, was intertwined with its shift to a form of power that could be extracted and privatized from the earth. Economic competition between capitalists, each dependent on private fossil fuels, also became intertwined with geopolitical competition between states. This has produced a constant stream of wars for oil, fueled by oil.

But there are contradictions in the oil economy. Despite the mobility of oil once it’s extracted, the process of extraction and refining is largely immobile. Fossil fuel extraction represents some of the largest industrial projects, requiring the longest term and most intensive investment of fixed capital of any sector; the tar sands is now the largest megaproject on the planet, and capitalists must operate projects for decades to get a return on investment. While capitalists often use the threat of mobility to extract concessions from workers, oil extraction is rooted where the oil is located and dependent on oil workers. This gives oil workers incredible potential power to shut down the key resource of the capitalist economy and strike a blow at state power. Throughout history, oil workers around the world have played a key role in anti-capitalist and anti-colonial rebellions.

Anti-capitalism, anti-colonialism

As Rosa Luxemburg observed in The Mass Strike, the political revolution in Russia in 1905 against the Tsar had its roots in “the great thunderstorms of mass strikes in South Russia in 1902 and 1903.” This included a mass strike by oil workers in Baku, which who won the eight-hour day in December 1904—a month before the 1905 revolution erupted. This was a dress rehearsal for the great revolution of 1917, which also included oil workers in Baku. At the centre of Muslim-majority Azerbaijan, an oppressed nation with the Russian empire, Baku was the site of a major conference linking worker struggles and national liberation movements.

As the American socialist report John Reed said at the 1920 conference, “Do you know how ‘Baku’ is pronounced in American? It is pronounced ‘oil’! And American capitalism is striking to establish a world monopoly of oil. On account of oil, blood is being shed. On account of oil, a struggle is being waged, in which the American bankers and the American capitalists attempt everywhere to conquer the places and enslave the peoples where oil is found…In Baku there are no more capitalists, and this oil no longer belongs to the capitalists. If this can be done in Baku, in Russia, why cannot such a social order to achieved in America and around the world?”

The Russian Revolution was part of a global wave of revolt: in 1917 American oil workers went on strike to unionize, while the Mexican revolution (including striking oil workers) ratified their constitution including a clause on nationalizing natural resources.

Oil workers were also part of strikes against Western control of oil in Iran the late 1940s—which encouraged Mossadegh to nationalize the industry in 1951. The US organized a military coup and imposed a brutal dictatorship. But in 1978 oil workers went on strike for both economic and political demands—including against the secret police, and against oil shipments to Israel. These were part of a mass revolution that toppled the Shah.

Because of their centrality to the capitalist economy, oil workers have been the target of counter-revolutionary regimes and imperialist wars—from Stalin in Russia and Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran, to US intervention in Iraq and Libya. As the president of the Iraqi Federation of Oil Unions explained in 2008, “Five years of invasion, war and occupation have brought nothing but death, destruction, misery and suffering to our people…Our union offices have been raided. Union property has been seized and destroyed. Our bank accounts have been frozen. Our leaders have been beaten, arrested, abducted and assassinated. Our rights as workers are routinely violated. This is an attack on our rights and the basic precepts of a democratic society.”

In the Egyptian revolution, it was strikes by workers at Suez—threatening the major artery of the oil economy—that finally drove Mubarak from power, and NATO intervened in the Libyan revolution when oil workers began taking control of the oil fields.

Health, safety and environment.

As well as being part of anti-capitalist rebellions, oil workers have also been central to occupational health and safety reforms—learning from and contributing to the environmental movement.

The early environmental movement focused on conservation and the impact of chemicals on wildlife—ignoring the workers who produced and were exposed to chemicals. The labour movement linked environmental and health concerns, and contributed to regulations in the 1970s. Following fatal air pollution from a factory in Pensylvannia, the Steelworkers became a driving force for the Clean Air Act. Following mine disasters and chronic lung diseases, coal miners mobilized to win the Mine Safety and Health Act. The United Farm Workers made opposition to pesticides central to farm workers unionizing. Declaring that “pesticide poisoning is more important today than even wages”, Cesar Chavez launched a grape boycott that highlighted health concerns, and contributed to banning DDT. And oil workers played a key role in the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

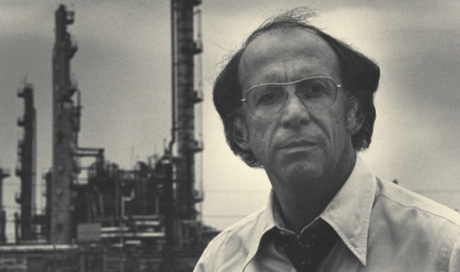

Anthony Mazzocchi was a WWII-vet and anti-war labour activist with the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers (OCAW) who saw the devastating cancer epidemic that struck Navajo uranium miners. Inspired by the ecologist Rachel Carson and working with Ralph Nader, he organized townhall meetings across the country where oil workers spoke out against the dangerous conditions in the workplace. He also spoke at the first Earth Day events in 1970. Whereas earlier lobbying failed to win health and safety regulation from Democrats, worker mobilization succeeded in extracting reforms from Republicans. Mazzocchi explained the lesson, which is important for today: ''What's incredible was the guy who was president then was Richard Nixon, which shows that when you build a big movement from down below, regardless of who's in the White House, you can bring about change.''

OCAW not only changed the law but transformed people’s understanding of the environment. As Mazzocchi’s biographer explained, “Before Mazzocchi, pollution was viewed largely as a problem of dumping and emissions, of where the bad stuff ended up—in the air, the water, the soil, in our food. Mazzocchi’s conceptual breakthrough was that pollution always starts in the workplace, and then moves into the community and the natural environment. Workplace pollution, therefore, was the source of environmental degradation, and only strict workplace controls on pollutants and toxic substances could adequately protect us from hazards.”

As Mazzocchi summarized, “You can’t be concerned about the general environment unless you’re concerned about the industrial environment, because the two are inseparable.” In 1973 OCAW workers went on strike to protect this shared environment. Amidst the speedups to fuel the Vietnam War, and cutbacks in maintenance, thousands of Shell workers went on strike for their health and safety. They demanded independent inspections, a health and safety committee, information on chemicals and illnesses and free medical examinations. As one oil worker explained, “we recognize that all the things that we have gained in the way of wages, and everything else—if you die getting them, they are not going to do you any good.” Unable to dent the profits of the oil giant that used helicopters to support its scab labour, OCAW called for a boycott of Shell. The “Shell No!” campaign mobilized workers across the country, from New York cab drivers who refused to refuel at Shell stations, to San Francisco longshore workers who refused to unload Shell oil.

It also included crucial support from major environmental organizations, who issued an open letter a week into the strike: “We have increasingly come to recognized that working people are among the hardest hit by the hazards of pollution in the workplace. If toxic substances are present in oil refineries, they most assuredly are spreading outside the plant walls to neighboring communities…This struggle is of historic importance in that it is the first time a major union has struck on what is fundamentally an environmental issue. It illustrates the shared concerns of workers and environmentalists about the quality of our environment, whether inside the plant or beyond its gates. We support the efforts of the OCAW in demanding a better environment, not just for its own workers, but for all Americans.”

The strike not only won the demands for safety committees and information on occupational hazards, but also built bridges between the labour and environmental movements. Neoliberalism worked to bomb those bridges, attacking union rights and blaming layoffs on environmental regulation to pit workers against environmentalists. As Mazzocchi lamented, “Corporate America has painted everyone into a classic dilemma. Now it’s jobs versus the environment. The worker has a choice between his livelihood and dying of cancer.”

But the alliance is reforming. In 2015 Shell workers went on strike again, and received support from Friends of the Earth, Sierra Club and 350,0org. As Labor Network for Sustainability explained in it, “Oil refinery workers are in the front line of protecting our communities against the environmental hazards of the oil industry. Their skill and experience is critical for preventing devastating explosions, spills, and releases . . . organized labor must recognize its shared interest with those vying for a healthier planet. As we work to protect the earth from climate change, it is particularly important that we advocate for the needs of workers in fossil fuel industries whose well-being must not be sacrificed to the necessity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Just transition

Oil workers have gone on strike against the profit-drive leading to spills and explosions, and also articulated a vision of how to move beyond oil. As a WWII-vet, Mazzocchi experienced the Gill Bill of Rights, which provided education and training for soldiers so they could transition from the trenches abroad into jobs at home. In the 1970s, he spoke with nuclear weapons workers about the contradictions of their job and the need for alternatives: “You’re either gonna use this weapon, and none of us will be around, or you’re gonna stop making it… Peace is going to break out. Then what are you going to do, march to demand more hydrogen bombs?”

Then in 1980 the government announced a Superfund to clean up polluted sites. If there was money to clean up pollution, there should be money to help workers transition out of polluting industries, and Mazzocchi called for a Superfund for Workers. Like the vets who were supported from their transition from military to civilian life, oil and atomic workers of his union should get full government support for the education and training required to transition from jobs that destroy the planet to those that preserve it.

This concept is now known as just transition, and oil worker activists continued to demand it. As oil sands worker Ken Smith said at the Paris climate conference in 2015, “We hope we’re seeing the end of fossil fuels for the good of everybody. But how are we going to provide for our families? We’re going to need some kind of transition.”

The climate justice movement is increasingly raising these demands. As the Leap Manifesto states, “we want training and other resources for workers in carbon-intensive jobs, ensuring they are fully able to take part in the clean energy economy. This transition should involve the democratic participation of workers themselves. High-speed rail powered by renewables and affordable public transit can unite every community in this country—in place of more cars, pipelines and exploding trains that endanger and divide us.” The recent CLC convention built momentum for Workers for the Leap, for unionized workers to push for just transition.

Uniting the democratic aspirations of oil workers for a safe job and clean environment with the broader labour and climate justice movements is part of building towards a mass transition in society, beyond the oil-dependent capitalist system.

Section: