What we think

You are here

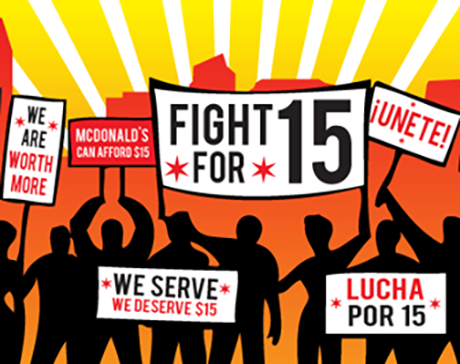

Socialists and the Fight for $15

October 1, 2016

Socialists have an important role to play in building working class solidarity and trying to prevent ideological fault lines from becoming fractures. That’s why it can be useful to think through some of the strategies currently being deployed to address income inequality. Importantly, these debates are emerging because a growing number of people are engaged and working to find solutions to very real problems. How socialists respond to these debates is important.

Basic Income

The Liberal government has introduced a basic income pilot project and many anti-poverty activists have welcomed this development, celebrating its widespread support on both the right and left of the political spectrum. Similarly, a number of well-respected, progressive academics have championed basic income as a means of accommodating the “new labour market realities.” Meanwhile, others on the far left have argued that the guaranteed basic income is a more radical approach than “merely” raising the minimum wage which, they argue, is “inherently low.”

Fortunately, other voices have been more critical. CUPE Ontario and OCAP’s John Clark have made crucial contributions to this debate emphasizing the implications that Basic Income proposals might have for social programs and services, especially in today’s context when the labour movement is not at its most militant.

While of course socialists support a decent income floor for all workers—with or without jobs—we must be careful not to let employers off the hook for wages and benefits. It’s why socialists fight not only for higher wages, but also for other forms of wages such as workplace pensions and benefits while also fighting for strong expanded CPP and QPP, public health care, medicare, housing, etc.

Those who support basic income, are important parts of the movement and they support the program for all the best reasons. They don’t yet see the risk that clever sections of the ruling class might use basic income as an excuse to cut other aspects of the social wage, such as housing, child care and more. For the Fight for $15, there is also a risk that the Liberals will counterpose basic income to raising the minimum wage which, alongside some modest labour law reform, might lead some to think that the Liberals are offering a more radical solution to income inequality than the movements.

Socialists want to build unity and solidarity as well as political clarity. Rather than simply opposing basic income (and by extension the people who support it) socialists can argue that basic income must go alongside a higher minimum wage, better social housing, child care and other strong social programs that workers rely on. We can argue that employers must not be let off the hook for providing decent work and that public resources ought not subsidize unsustainable business models built on poverty-level wages. By posing the arguments in this way, it might be possible keep united the forces that want change while setting the stage for exposing the modus operandi of class rule.

Living Wage

Like basic income, proponents of the living wage see this campaign as an important mechanism to raise the horizons of people who want to see social and economic justice. Rather than just a “minimum” wage, they argue, we should be defining and measuring quality of life so that wages allow workers to live well, not just stay alive. This moral edge makes it an attractive slogan for unions fighting for better wages and anti-poverty activists supporting the working poor. It is also, in part, a challenge to the low-horizons of the traditional “left” – rather than just fighting to oppose something, they seek to raise the hopes and expectations of a new generation of workers.

At the same time, workers get confidence when self-declared living wage employers speak out, because it helps undermine the persistent message from employer organizations such as the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses that any increase in the minimum wage or improvements in working conditions will cause job loss, inflation or otherwise ruin the economy. When there are splits in the capitalist class, it creates space for workers to speak out, get active and ultimately push for more.

Unfortunately, there are also weakenesses in the methodology behind the formal living wage campaigns and while it is intended to support higher wages for some, it has also be used to argue for lower wages for others, as Maclean’s magazine did in September 2014 and as the National Post argued most recently (September 2016). Progressives should be cautious about applying means-testing to wages. Afterall, the historical justification for lower wages for women (including legislated lower minimum wages) was based in part on the assumption that women would have husbands and therefore fewer expenses. Similarly, assumed lower expenses for younger workers continues to be used to justify two-tier minimum wages in Ontario – 70 cents less an hour for students under the age of 18.

There is a further concern that the formula used to calculate the living wage inadvertently counterposes social programs to wages. For instance, if child care is considered an expense justifying a particular living wage, then winning free universal childcare would have the effect of reducing the level of calculated living wage. And in at least one community, the living wage rate was reduced in response to a campaign victory that resulted in lower public transit rates.

In practice, there are other problems with a formula that would pay workers based assumed living expenses in a given geographic location. Many workers live in one area but work in another – should workers be paid differently depending on where they live?

There is also a risk that, without a unified campaign to raise the floor for all workers, the wide range of different living wage rates could fragment the unity necessary to achieve a legislated wage floor across the province, especially where the living wage calculations are actually lower than $15 an hour (as it is in Brantford-$14.85; Hamilton-$14.95; and Windsor-$14.15).

These kinds of considerations help us to understand why union collective agreements generally avoid tying wages to assumptions about workers’ expenses, and why generally speaking tiered wages undermine solidarity.

Again, socialists want to build the confidence and solidarity of the movement and how we respond to these debates are important, both for the ideological clarity of the movement but also for its numeric strength. For many people, the living wage is synonymous with a decent, better, liveable minimum wage. Such people are a crucial part of the movement and we want to be fighting alongside them.

For all these reasons, socialists don’t have to counterpose the living wage to the minimum wage, but it can fight to make sure that the Fight for $15 has a profile while also patiently identifying some of the risks in focusing on employers instead of workers, of introducing excuses to pay workers less or reinforcing neoliberal notions of targeted funding via means-testing for wages.

Join the rally for decent work october 1, Queen's Park at noon

Section: