Features

You are here

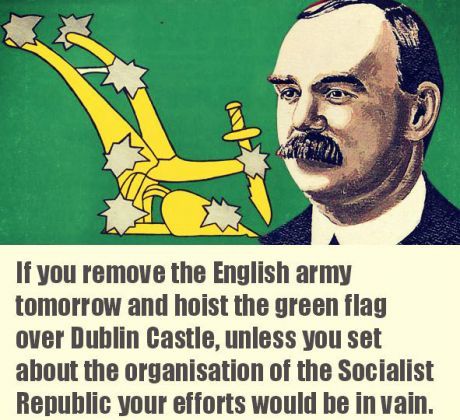

The Easter Rising and the politics of James Connolly

March 27, 2016

The Easter Rising of 1916 fused together national liberation, women’s liberation and workers’ struggles, as can be seen from the theory and practice of one of its leaders, James Connolly.

James Connolly was born in 1868 and was a key figure in early 20th century Irish politics. He was a leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, a founder of the Irish Citizens Army, and a leader during the rising of 1916—for which he was executed. His writings, a hundred years later, still carry lessons for struggles today.

National liberation

As Connolly wrote in 1897 in the article Socialism and Nationalism, the role of national liberation struggles should fuse independence with broader social and economic change:

“The Republic I would wish our fellow-countrymen to set before them as their ideal should be of such a character that the mere mention of its name would at all times serve as a beacon-light to the oppressed of every land, at all times holding forth promise of freedom and plenteousness as the reward of their efforts on its behalf.

“To the tenant farmer, ground between landlordism on the one hand and American competition on the other, as between the upper and the nether millstone; to the wage-workers in the towns, suffering from the exactions of the slave-driving capitalist to the agricultural labourer, toiling away his life for a wage barely sufficient to keep body and soul together; in fact to every one of the toiling millions upon whose misery the outwardly-splendid fabric of our modern civilisation is reared, the Irish Republic might be made a word to conjure with – a rallying point for the disaffected, a haven for the oppressed, a point of departure for the Socialist, enthusiastic in the cause of human freedom.

“This linking together of our national aspirations with the hopes of the men and women who have raised the standard of revolt against that system of capitalism and landlordism, of which the British Empire is the most aggressive type and resolute defender, should not, in any sense, import an element of discord into the ranks of earnest nationalists, and would serve to place us in touch with fresh reservoirs of moral and physical strength sufficient to lift the cause of Ireland to a more commanding position.”

As he warned nationalists who only fought for independence, “If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs.”

Women’s liberation

As the founders of the Irish Women’s Franchise League described, James Connolly was also “the soundest and most thoroughgoing feminist among all the Irish labour men.” In his chapter on women’s rights in his 1915 book The Re-Conquest of Ireland, he condemned women’s oppression, from exploitation at work to unpaid labour at home:

“The worker is the slave of capitalist society, the female worker is the slave of that slave… Wherever there is a great demand for female labour, as in Belfast, we find that the woman tends to become the chief support of the house. Driven out to work at the earliest possible age, she remains fettered to her wage-earning—a slave for life. Marriage does not mean for her a rest from outside labour, it usually means that, to the outside labour, she has added the duty of a double domestic toil. Throughout her life she remains a wage-earner; completing each day’s work, she becomes the slave of the domestic needs of her family; and when at night she drops wearied upon her bed, it is with the knowledge that at the earliest morn she must find her way again into the service of the capitalist, and at the end of that coming day’s service for him hasten homeward again for another round of domestic drudgery. So her whole life runs—a dreary pilgrimage from one drudgery to another; the coming of children but serving as milestones in her journey to signalise fresh increases to her burdens…

“Of what use to such sufferers can be the re-establishment of any form of Irish State if it does not embody the emancipation of womanhood. As we have shown, the whole spirit and practice of modern Ireland, as it expresses itself through its pastors and masters, bear socially and politically, hardly upon women. That spirit and that practice had their origins in the establishment in this country of a social and political order based upon the private ownership of property, as against the older order based upon the common ownership of a related community.”

Connolly spoke at meetings in support of women’s suffrage, and through his union the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), provided support for suffragists against right-wing attacks. He also supported women workers, whose militancy he identified as key to the class struggle:

“The development in Ireland of what is known as the women’s movement has synchronised with the appearance of women upon the industrial field… In Ireland the women’s cause is felt by all Labour men and women as their cause; the Labour cause has no more earnest and whole-hearted supporters than the militant women…

“None so fitted to break the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what is a fetter. In its march towards freedom, the working class of Ireland must cheer on the efforts of those women who, feeling on their souls and bodies the fetters of the ages, have arisen to strike them off, and cheer all the louder if in its hatred of thraldom and passion for freedom the women’s army forges ahead of the militant army of Labour. But whosoever carries the outworks of the citadel of oppression, the working class alone can raze it to the ground.”

Join the conference Ideas for Real Change: Marxism 2016, including the opening panel “The Easter Rising of 1916: 100 years of resistance,” with Sid Ryan, past president of the Ontario Federation of Labour, and Carolyn Egan, leading member of the International Socialists and president of the Steelworkers Toronto Area Council. Register today and join/share on facebook

Section: