Columns

You are here

Capitalism and precarity

April 22, 2015

A recent interview with American socialist Charlie Post on Jacobin questions one of the common sense ideas among many sections of the left today—the notion of the precariat. Essentially this is the notion that there is an underclass of workers who receive minimum wage or lower, have no benefits and work part-time. According to the conventional wisdom this group is completely separated from workers who have full time employment and more secure working situations.

The underlying logic of this argument is that neoliberal capitalism has triumphed over ordinary workers’ ability to fight to set the terms and conditions of their exploitation, that workers in unions with higher wages and good benefits have been “bought off” and have left the “underclass” behind, and that the only option is for this underclass to fight on alone, most often outside the traditional union structures. By extension, this theory of the precariat also posits the “labour aristocracy” as being primarily male, white and existing in the rich Western countries.

Fight for $15 and a union

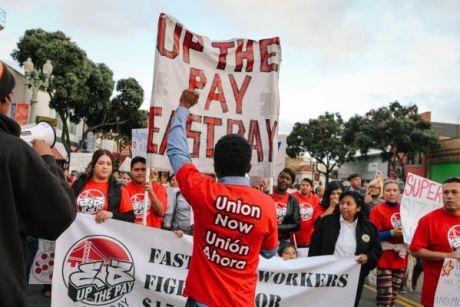

Recent events in North America put the lie to these theories of despair. On April 15 working people across North America (and the world) demonstrated and went on strike for two demands: a $15 minimum wage and fairness, including the right to form a union.

Across the US in recent months we have seen low-paid workers (disproportionately women and people of colour) rise up against employers like Walmarts and McDonalds, whose enormous profits depend on their cheap labour.

The fight for $15—which has the support of unions like SEIU and UFCW—has galvanized the entire labour movement in a way that we haven’t seen for decades. It is simply not true that there is a privileged group of workers in some mythical workplaces somewhere immune to the downward pressures of rampant neoliberalism.

All you need to do is look at the incredibly low level of unionism inside the US to understand that whether you work in an auto plant or a McDonald’s you cannot be sure about your future, about paying the rent or about the future of your children.

In Canada there is a higher rate of workers in trade unions, which is a good thing, but this trend is moving downward with the loss of thousands of manufacturing jobs over the last few years.

As the Jacobin interview proclaims, “We are all precarious now.” What does this mean? It doesn’t mean that there is no difference between the situation of a worker who is in a union and has some benefits and some kind of job security and a worker who toils for minimum wage or less with no job security and part-time hours.

But it’s necessary to see that these workers have a common interest in defending each other’s ability to organize, to demand decent wages and working conditions and to fight back against vicious bosses.

Oppression and precarity

Low-paid Black, Latino and white workers in the US are fighting exactly for the right to organize unions in their workplaces and to demand better wages and conditions. By so doing they are also fighting for their brothers and sisters already in unions to maintain what they have won and to stop the slide of wages and conditions that has been ongoing for the last 30 years.

Their struggles can also shake the complacency of the trade union bureaucracy, who often go along with the notion of precarious work and the impossibility of fighting global capitalism, because it means that they don’t need to organize a real fightback against the attacks on the working class.

It is definitely true that oppression (in the form of racism and sexism) means that workers of colour and women are often at the bottom of the heap when it comes to the kind of jobs that are available to them. You can see this from the participation in the April 15 rallies and from those taking the lead in the walkouts and one-day strikes of recent months.

As McDonald’s worker Katherine Cruz said at the April 15 rally in Boston, “We work really hard to make $8.75 and not be able to live. I feel like we should all—not only McDonald’s, not only fast-food workers—everyone that lives off minimum wage should make more, so we can all support our families, support ourselves.”

The fight for a decent minimum wage is a fight for the entire working class because the downward pressure on wages and conditions affects us all. In February 1917 the Russian Revolution was launched by a group of women on International Women’s Day who stormed the bakeries demanding bread for themselves and their families. Their action was the beginning of a movement of the whole class of Russian workers who would eventually storm the barricades and begin to shape a new society where they hoped oppression and exploitation could be ended forever.

Although their revolution was eventually destroyed by the joint forces of Stalinism and military opposition by 14 capitalist countries, the goal of ending exploitation and oppression is alive and well today in the hearts and minds of those fighting for their right to a decent minimum wage, to be able to join unions alongside their sisters and brothers and to so much more.

If you like this article, register for Rage Against the System, a weekend conference of ideas to change the world, April 24-26 in Toronto. Sessions include “Why is capitalism in crisis,” “Labour and the fight against austerity,” and “Festival of the oppressed: the history of the Russian revolution.”

Section: