Columns

You are here

Capitalism and the family

March 2, 2015

The theme of this year’s International Women’s Day March and Rally in Toronto is “Our Bodies. Our Territories. Our Communities.” This is a great banner that brings together the question of control and the lack of control women have over our bodies, linked to a similar lack of control indigenous women and men have over their land, wedded to the lack of control we all feel in terms of how we live our lives.

Since the early days of the Second Wave Women’s Movement (of the 1960s and 1970s) and long before, the question of control over our bodies has been a fundamental question for women seeking liberation. This has to do with the role of women inside the nuclear family under capitalism, which tends to enforce and reinforce the idea that women’s fundamental role in society is that of mother and caregiver to the next generation of workers. And, in spite of all the advances that women have made through our own struggles, often allied with our brothers in the union movement, the family continues to be the dominant ideology peddled by right-wing governments and media alike.

Of course, it is true that there have been major advances for women in the arenas of education, entry into non-traditional jobs and most importantly around the question of access to contraception and abortion. If a woman has no control over her reproductive life, over decisions about when and with whom to have children, she can have little control over other aspects of her life. Over the last few years, though, it’s become clear that any gains we have made are also under constant threat because of the economic system we live under—capitalism. The modern nuclear family as we know it today was solidified as an institution of use to capital during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century.

The nuclear family

At the time, the growth of industrial capitalism was actually killing working class family life, since it was pulling all family members (including pregnant women and children) in to the factories and mines. Women were dying in childbirth and children were subject to long working hours and horrendous conditions, as of course were men and women as well. There was no real family life.

This frightened some capitalists, who realized that if there was no stable family life, no ability for people to regenerate and rest for the next working day, they were going to kill the goose that laid the golden egg of profits. Their fears came together with the desires of working class people who fought for some protections for women and children (and men), so that they would stop dying in the workplace. Working class people wanted to live lives with some joy, some possibility of sharing their lives with the people they loved, some respite from the inhumane round of work, eat, sleep.

As Marx said, “Human beings make history, but not in conditions of their own choosing.” So it was that workers won struggles around advances such as a shorter working day and instituting child labour laws. However, at the same time, the nuclear family, with father as the head of the household and mother at home caring for children, became the norm and served to imprison women inside the family hearth.

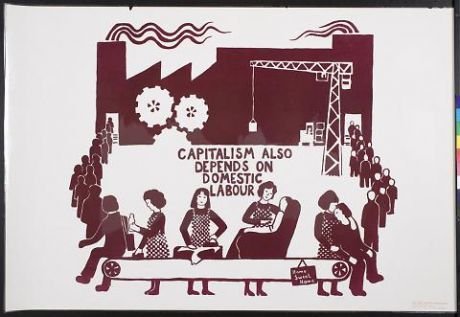

This was so even if the so-called family wage—supposedly paid to men so that women could stay at home and look after children—was never a reality for working class families. Working class women have always had to seek employment outside the home, usually in low-paid, ghettoized jobs, in order for the family to survive. On top of this work outside the home, capitalism constantly pushes the idea that women—whether they work for pay or not—are the ones who are and should be overwhelmingly responsible for housework and childcare.

This does a great service to the bosses, since they profit from the surplus value they extract from women’s wages at work and also from all the unpaid labour it requires to bring up the next generation of workers. This ideology is especially useful in periods of economic crisis, as we are living through today, when governments are removing more and more work from the public sphere (cuts to healthcare, services for kids and families, services for the elderly, etc.) and foisting it onto individual families—and disproportionately onto individual women in those families.

It is no wonder the family—which we are led to believe should be the one place where we can expect to find love and caring—is often a cauldron of abuse and unhappiness. The pressures on the family to provide a humane oasis in a society based on greed, profit for the few and destruction of the very environment we depend on to survive, are enormous.

Alternatives

But things don’t have to be this way. It is neither fair nor necessary that we continue to accept the way things are under capitalism. Just as indigenous people across Canada are resisting the Harper government and the priorities of that government (creating the sink hole of the Tar Sands, which is destroying indigenous families, their land, their livelihood at the same time it is polluting the planet) we can join together on this IWD to pledge together to build the new society and new families we need to survive. In order to do that, though, we will ultimately need to get rid of a system whose priorities have nothing to do with real choices for women or for any of us.

The early years of the Russian Revolution show a glimpse of what’s possible. Beginning on IWD in 1917, women made historic gains (abortion and divorce on demand, collective kitchens and crèches) as part of a revolutionary transformation of society—before it was destroyed by invading armies and internal counter-revolution. Alexandra Kollontai was a leading revolutionary who theorized about women’s liberation in the transition from capitalism to socialism as these changes were unfolding.

As she explained in Theses on Communist Morality in the Sphere of Marital Relations, written in 1921, “Family and marriage are historical categories, phenomena which develop in accordance with the economic relations that exist at the given level of production. The form of marriage and of the family is thus determined by the economic system of the given epoch, and it changes as the economic base of society changes… In the era of private property and the bourgeois-capitalist economic system, marriage and the family are grounded in (a) material and financial considerations, (b) economic dependence of the female sex on the family breadwinner – the husband – rather than the social collective, and (c) the need to care for the rising generation.”

But under socialism, “The external economic functions of the family disappear, and consumption ceases to be organised on an individual family basis, a network of social kitchens and canteens is established, and the making, mending and washing of clothes and other aspects of housework ‘are integrated into the national economy… The economic subjugation of women in marriage and the family is done away with, and responsibility for the care of the children and their physical and spiritual education is assumed by the social collective… Once the family has been stripped of its economic functions and its responsibilities towards the younger generation and is no longer central to the existence of the woman, it has ceased to he a family. The family unit shrinks to a union of two people based on mutual agreement.”

As Engels wrote in his groundbreaking work, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, socialism and the material conditions it ushers in will allow everyone to define their relationships, not based on the needs of a system based on profit, but on their own desires and needs, in community with others: “What we can now conjecture about the way in which sexual relations will be ordered after the impending overthrow of capitalist production is mainly of a negative character, limited for the most part to what will disappear. But what will there be new? That will be answered when a new generation has grown up…they will care precious little what anybody today thinks they ought to do; they will make their own practice and their corresponding public opinion about the practice of each individual – and that will be the end of it.”

Join Toronto IWD, Saturday March 7: 11am rally at OISE, 1pm march to Ryerson

Section: