What we think

You are here

Unfair elections: their democracy and ours

April 7, 2014

Since Harper’s Tories came to power, their disdain for democracy has been a running theme.

From the 2009 prorogation of Parliament to avoid the scandal over the treatment of Afghan detainees, to the robocalls of the 2011 federal election (when the Conservative Party voter database was used to identify non-Conservatives and give them false information about polling places) to the cover-up of the corruption of Senate appointees: there is no love lost between Harper and the democratic process.

Unfair Elections Act

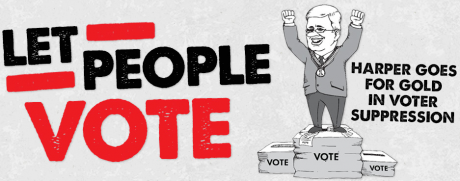

And now Bill C-23, the so-called “Fair Elections Act,” threatens to make voter identification harder and prohibit Elections Canada from engaging in any activity that would encourage people to exercise their franchise.

The elimination of vouching and of the use of voter information cards could have an impact similar to the suppression of already marginalized, racialized and low income voters in the US. In the 2011 Canadian federal election, 73 per cent of youth, Indigenous people and seniors voted using voter information cards, and 120,000 people voted through the voucher system.

The Act uses trumped-up concerns over “voter fraud” to scapegoat voters while diverting attention from the actual election fraud by the Tories in 2011. The Act would prevent Elections Canada from publicly reporting on election fraud, and strip the Commissioner of Elections Canada of investigative powers, perhaps making it easier for the “Pierre Poutines” of the world to get away with things like the fraudulent robocalls.

And beyond even this, the Act would cancel all Elections Canada’s research, democratic outreach and public education programs. This fits with the Harper government’s goal of a public disengaged from information in general, which they have enacted through the elimination of the long-form census, cuts to Statistics Canada and to basic scientific research, and the silencing of NGO’s.

An open letter from 19 professors from the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark and Ireland in the Globe and Mail stated: “We believe that this Act would prove be deeply damaging for electoral integrity within Canada, as well as providing an example which, if emulated elsewhere, may potentially harm international standards of electoral rights.” In addition to concerns over voter suppression and investigation of real fraud, they warn the bill would expand “the role of money” in elections by allowing parties to exempt fundraising activities from campaign spending, raising certain donation limits, not requiring parties to document their expenses and “increasing the influence of personal wealth” by allowing people to donate more to their own campaigns.

Defending and expanding democracy

“Let People Vote!”, a campaign led by the Canadian Federation of Students, the Council of Canadians, and Leadnow.ca, has led rallies at Tory MPs’ offices, collected 80,000 names on a petition, and held a national day of action against the Act.

There is no question that the Fair Elections Act must be opposed, and that defeating it would give confidence to all those who oppose the Harper political agenda in general.

But the recurring debates over different aspects of the democratic system beg the question of how to ensure that progressive movements continue to link the defence of our current electoral and parliamentary rules, and progressive calls for their reform, to the critical issues that underlie what democracy means.

This question emerged in the anger that exploded over the prorogation of Parliament in 2009. At the time, not only did Harper say that Canadians don’t care about Afghan detainees but also that Parliament creates “instability,” getting in the way of the real work to fix the economy. While many were rightly moved to take to the streets in the rallies against prorogation because the Tories were admitting they saw Parliament as a nuisance, it was the killing of the committee looking into the treatment of Afghan detainees that was the real story. In other words, it wasn’t really Parliament that was creating “instability” but popular opposition to the war in Afghanistan.

Similarly, the recent debate over Senate reform has been a conduit not only for popular disgust with corruption but with growing social inequality and the hypocrisy of government austerity. Should the Senate be reformed or abolished? The question is actually much bigger than that, since Senate is not the only trough at which the 1% are feeding at the expense of the majority of people in Canada.

Progressive movements in Canada and Quebec have raised other demands for democratic reform, notably for proportional representation instead of the current first-past-the-post system that prevents the popular vote from being reflected in the result of elected seats. But again, this reform as an end in itself could benefit small right-wing fringe parties or conservative voting patterns, as it has in parts of Europe. As a demand it has to be framed not as an abstract democratic right but as a tool to push the political spectrum to the left.

Building the movement outside Parliament

All of these demands for reform or defence of the democratic rights we do have must be judged by how they advance movements of resistance that go past the rules of Parliament. Low voter turnout does not just indicate barriers to voting, voter suppression or apathy, but the reality that often there is little meaningful to vote for. However, any attempt to dictate who gets to vote and who doesn’t is what must be opposed.

The Fair Elections Act is referred to as US-style voter suppression, and there are certainly echoes of that. But voter suppression in the US is about much more than Republican suppression of the Democratic vote. It is about the history of slavery and civil rights. The voter registration drives in the 1960s, when hundreds of students and activists joined “Freedom Rides” into the US South to defend the right to vote for African-Americans, were part and parcel of the civil rights movement as a whole.

The key to all of this is to recognize that modern democracy, whether Parliamentary or republican, is a historical creation full of contradictions. The right for all to cast a ballot, whether or not you own property, and regardless of gender and race, was hard-won and must be defended. But in those historical battles for suffrage, there were always debates over whether the right to vote alone is enough.

One of the slogans in the 2009 anti-prorogation campaign was “Harper: get back to work.” But is that really what we wanted? The slogan “Let People Vote!” is much better. It is our role that is at stake. But the key is to remind ourselves why the right to vote really is important.

It is a right that is not just important on election day. It is a right that reminds those who rule, and those of us that don’t, that the balance of power can change. That potential for change and “instability” beyond Parliament is what really motivates Harper to change the rules of the game. And it is what should motivate us in how we resist it.

Section: