Arts

You are here

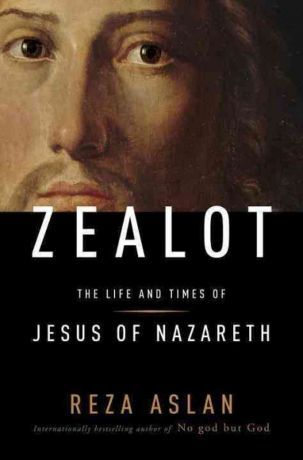

Jesus was a revolutionary

December 22, 2013

In his short and readable best-seller, former evangelical Christian Reza Aslan makes a compelling argument: that Jesus was a Jewish revolutionary executed for challenging Roman occupation and the Temple elite, who was subsequently detached from his political and earthly roots and turned into a celestial being.

These claims are not new, but Aslan presents them in an accessible and engaging way, describing the economic, political and religious context in which Jesus lived in an attempt to understand the historical figure and the religion that emerged after him. It was Aslan’s own evangelical journey that provoked this book, and it is written with the same passion: “The more I probed the Bible to arm myself against the doubts of unbelievers, the more distance I discovered between the Jesus of the gospels and the Jesus of history—between Jesus the Christ and Jesus of Nazareth…The more I learned about the life of the historical Jesus, the turbulent world in which he lived, and the brutality of the Roman occupation that he defied, the more I was drawn to him.”

Zealous resistance to Roman occupation

Aslan begins by describing the colonial and class dynamics of first-century Palestine: a brutal Roman occupation that crushed dissent, imposed taxes and relied on an alliance with a wealthy Temple elite who benefited from economic inequality. In this context there were waves of Jewish nationalist resistance, many before and after Jesus, who used religious zeal to challenge both the occupation and the complicity of the local elites.

This is the context for the poor Jewish worker known as Jesus of Nazareth: “Six days a week, from sunup to sundown, Jesus would have toiled in the royal city, building palatial houses for the Jewish aristocracy during the day, returning to his crumbling mud-brick home at night. He would have witnessed for himself the rapidly expanding divide between the absurdly rich and the indebted poor…He certainly would have been familiar with the exploits of Judas the Galilean .”

Though almost nothing is known about the historical Jesus, Aslan uses the historical context in which he lives to build his case: “There are only two hard historical facts about Jesus of Nazareth upon which we can confidently rely: the first is that Jesus was a Jew who led a popular Jewish movement in Palestine at the beginning of the first century CE; the second is that Rome crucified him for doing so…The Jesus that emerges from this historical exercise—a zealous revolutionary swept up, as all Jews of the era were, in the religious and political turmoil of first-century Palestine—bears little resemblance to the image of the gentle shepherd cultivated by the early Christian community. Consider this: Crucifixion was a punishment that Rome reserved almost exclusively for the crime of sedition…Jesus’ crime, in the eyes of Rome, was striving for kingly rule (ie treason), the same crime for which nearly every other messianic aspirant of the time was killed.”

“Woe to you who are rich”

Through this lens, Aslan then highlights the New Testament passages that reveal this radicalism. Part of this argument involves translation: Aslan writes that Jesus’s statement that “My Kingdom is not of this world” is better translated as “not part of this order/system”—ie not a celestial place but a radically different earthly order—and the criminals executed alongside Jesus were lestai, meaning bandits, the term the Romans used for rebels.

Part of this argument involves highlighting Jesus’s attack on the Temple and statement to “Give back to Caesar the property that belongs to Caesar, and give back to God the property that belongs to God” (ie end the Roman occupation). As Aslan writes, “Look closely at Jesus’s words and actions at the Temple in Jerusalem—the episode that undoubtedly precipitated his arrest and execution—and this one fact becomes difficult to deny: Jesus was crucified by Rome because his messianic aspirations threatened the occupation of Palestine, and his zealotry endangered the Temple authorities.”

Part of Aslan’s argument also quotes less known passages of Jesus to build a case of what his central message was: “The Kingdom of God is not some utopian fantasy wherein God vindicates the poor and the dispossessed. It is a chilling new reality in which God’s wrath rains down upon the rich, the strong, and the powerful. ‘Woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you who are full, for you shall hunger. Woe to you laughing now, for soon you will mourn’ (Luke 6:24-25)…Saying ‘the Kingdom of God is at hand,’ therefore, is akin to saying the end of the Roman Empire is at hand. It means God is going to replace Caesar as ruler of the land. The Temple priests, the wealthy Jewish aristocracy, the Herodian elite, and the heathen usurper in distant Rome—all of these were about to feel the wrath of God. The Kingdom of God is a call to revolution, plain and simple.”

From Jewish revolutionary to Christian deity

How then to explain the transformation from a Jewish revolutionary based in Palestine to a Christian deity whose main church is in Rome? Aslan begins with history: a generation after Jesus’s death the Romans laid a savage siege to Jerusalem, after which Jesus’s followers were increasingly Greek-speaking Jews in the diaspora, writing for a Roman audience: “The Christians felt the need to distance themselves from the revolutionary zeal that had led to the sacking of Jerusalem, not only because it allowed the early church to ward off the wrath of a deeply vengeful Rome, but also because, with the Jewish religion having become pariah, the Romans had become the primary target of the church’s evangelism. Thus began the long process of transforming Jesus from the revolutionary Jewish nationalist into a peaceful spiritual leader with no interest in any earthly matter. That was a Jesus the Romans could accept, and in fact did accept three centuries later.”

Aslan then goes back to the New Testament trying to prove how the historical Jesus was buried with scripture: successive gospels reduced Jesus’s mentor, John the Baptist, and his brother the apostle James, in order to construct a divine being born of a virgin; the story of Pontius Pilate’s encounter with Jesus was fabricated to blame the Jews and absolve the Romans; and Paul’s writings, which clashed with the early Christians, severed Jesus from his Jewish roots and turned him into a God, came to dominate the New Testament.

Debates

All this is not plain and simple—to explain in 200 pages the contradictions and development of a religion 2000 years old—and it is not surprising that there have been many critiques of Aslan for his simplistic historical and religious arguments, and his choice of some sections of the Bible as fact and others as fiction. Part of this is the nature of religious interpretation, which Aslan’s book has certainly helped popularize.

Beyond the serious critiques of the book, the best publicity was the notorious Islamophobic “interview” with Fox News—where an irate anchor demands to know why Aslan, an academic who happens to be Muslim, should be writing on Jesus. What angers the right is not only Aslan’s Iranian background, and his newfound Muslim faith, but his argument about the radicalism of Jesus. While this argument might be old, it is reappearing in a new context of austerity and resistance, where even the Pope is denouncing free market economics. It is uncomfortable for some but inspiring to others, to hear that that revolution is the answer to the question “what would Jesus do?”

Section: