Features

You are here

Do you know about Canada's "Indian hospitals"?

December 22, 2013

Thanks to Idle No More members and the many indigenous activists before them, non-indigenous Canadians are learning more about their shameful colonial history and mistreatment of indigenous peoples. While there is growing awareness of funding inequities in health and education, the horrific legacy of residential schools (including disproportionate levels of disease, unemployment and incarceration) and the removal of indigenous children away from their families, much less is know about Canada’s “Indian Hospitals.”

Laurie Meijer Drees, Co-Chair of the First Nations Studies Department at Vancouver Island University, has done a fine job of addressing this with her highly recommended book, Healing Histories: Stories from Canada’s Indian Hospitals (University of Alberta Press 2013). This article summarizes some of the book’s highlights.

Ms. Drees undertook a traditional, respectful approach in gathering the stories of individuals who had worked in or been placed in these hospitals. The details in the stories help bring to life this almost secret part of the history of Canada’s “universal” health care system in the post-World War II period.

"Indian hospitals"

But first, some background: “As early as 1914, sections of the Indian Act allowed the government to apprehend patients by force if they did not seek medical treatment.” “Registered Indians” had to seek treatment from a “properly qualified physician,” which from the government’s point of view ruled out traditional healers. As with residential schools, we can see this as an action by government to both control the lives of First Nations peoples and to negate the worth of their traditions.

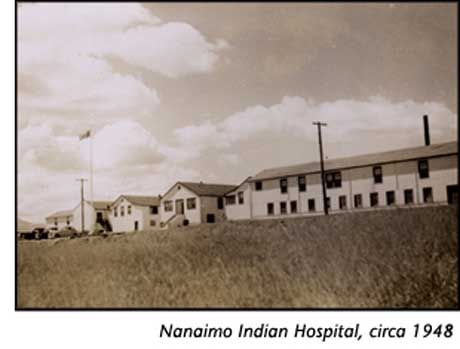

The story of Indian hospitals is inextricably linked to that of tuberculosis (TB): “infection rates for TB in Canada’s registered Indian population were ten times the national average in 1944” and remained so into the 1960s. This disparity was caused by overcrowding in residential schools, plus poor living conditions on reserves and in remote communities. It looked like First Nations and Inuit patients were receiving the same medical treatment as non-First Nations (although First Nations patients were not treated in sanatoria until the 1940s), including rest regimes, surgeries and drugs. The big problem, however, was that these treatments were not made available near, let alone in, the communities where affected First Nations peoples lived. Instead, they had to travel long distances, away from home, family and a familiar language, for TB treatment. After 1945, they were put in segregated facilities (“Indian hospitals”) that denied the use of traditional healing methods. And, to top it all off, (no surprise here), the standards in these hospitals was less than that of other hospitals in the country, in terms of care and especially consent. As we saw with residential schools, where starvation was used to “test” the resilience of pupils, in Indian hospitals, patients were often “tested” for new drugs or treatments.

The largest of these hospitals were in BC and Alberta, with between 250 and 500 beds. The government’s motives included its continued goal of attempting to assimilate First Nations peoples, as well as keeping other Canadians healthy, i.e. there was less interest in treating TB to ensure the health of First Nations peoples than in ensuring everyone else was OK, protected from this contagious disease.

Drees book shares heartbreaking stories of both children and adults who suffered on many levels: their illness, separation from their families, long stays in hospital, and mistreatment by staff.

Resistance

But there was resilience too. Unlike residential schools, Indian hospitals became a place of employment for First Nations people. Some studied and became nurses or x-ray technicians, while others took training to become aides. But, as Drees notes, “At this time some Canadian schools refused to allow visible minorities to enrol in their nursing programs, therefore, it was not unusual for Aboriginal women to enter nurse training programs in the United States, which were more open to women of colour.” Because employment records did not consistently indicate the cultural background of employees, it is unknown how many indigenous people sought training and employment in Indian hospitals, or in other health facilities on reserve or in urban settings from the 1950s to 1970s. But, “by the 1980s more than three thousand community health representatives and health liaison workers worked at the community level”, and many more at professional levels on band lands and in urban settings.

In some ways, however, this employment pattern can be seen as an early mechanism by which First Nations reclaimed their authority for looking after their own people. Boosted by the Red Power movement in the late 1960s and 1970s, First Nations asserted their right to health care that addressed their needs, with personnel and in ways and that respected their traditions.

Today those steps continue. First Nations in BC, for example, successfully argued for a First Nations Health Authority, which is about to see the transfer of hundreds of positions and hundreds of millions of dollars in funding transferred to it from Health Canada. It is expected that the Authority will ensure services on reserve are more culturally relevant, more prevention-focused and more community-based.

Reading this book is a reminder of yet another chapter in the story of Canada’s colonization of indigenous peoples, as well as the continuing fight back.

Section: