Features

You are here

Black history: remembering Bayard Rustin

February 15, 2013

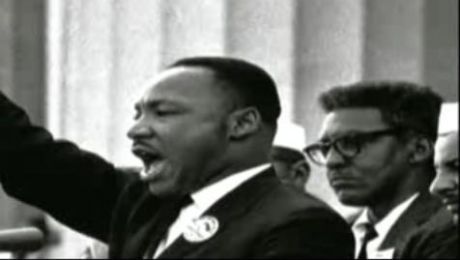

Which African-American activist was beaten for sitting in a white-only section of a bus in 1942, resisted WWII, pioneered the freedom rides, led the War Resisters League, organized anti-nuclear protests, and was the main organizer of the historic 1963 March on Washington? While he mentored Martin Luther King, inspired Stokely Carmichael, met with Jawaharlal Nehru and Kwame Nkrhumah, debated Malcolm X, and even briefly sang with Paul Robeson, Bayard Rustin (behind King in the photo above) has been virtually erased from history—mainly because he was an openly gay socialist.

The Civil Rights Movement is often presented as a spontaneous outburst, with no connection to movements and activists before it; it is often reduced to an isolated view of Martin Luther King, frozen in time in 1963 and separated from anti-war, labour, gay and socialist activists. Rustin represented all these, and attempts to restore his place in history—from the moving documentary “Brother Outsider”, the excellent biography “Lost Prophet”, and his partner’s ongoing efforts in the lead up to the march’s 50th anniversary this August 28—are part of uniting movements against racism, homophobia, war and exploitation.

Early influences and campaigns

Rustin was born in Pennsylvania in 1912 to a Quaker family active in the NAACP, which provided him with pacifism and a quest for justice. He learnt about class politics and organizing from the Communist Party, which he joined in the 1930s when he moved to Harlem. As he wrote later on, “I learned many of the most important things I learned about organization and writing clearly from my experience as a communist.”

But when Stalinism purged the Communist Party of its revolutionary politics, and dropped anti-racism in order to support WWII, Rustin left. He went to work for two leading activists on the anti-Stalinist left: A Philip Randolph (a black trade union militant whose threats of a 1941 March on Washington forced Roosevelt to desegregate defense employment), and AJ Muste (a white, labour organizer and Christian pacifist who founded the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress on Racial Equality—taking pacifism and civil disobedience to fight racism). Working with Randolph and Muste, Rustin gained experience advocating multiracial nonviolent civil disobedience, and linking antiwar and anti-racism with class politics.

In 1942 Rustin was beaten for sitting down in a white-only section of a bus, and in 1944 went to jail for two years for resisting WWII—along with thousands of others, which Muste called the “shock troops of pacifism.” He used the opportunity to launch a campaign to desegregate the prison cafeterias, but was persecuted for being openly gay—and got no support from Muste. Upon his release from jail, Rustin pioneered the precursor of the Freedom Rides—organized multiracial teams testing the bus desegregation law with CORE, the War Resisters League (WRL), other socialists, and Ella Baker (another unsung hero of the Civil Rights Movement). They organized two dozen tests across four states, and as Rustin wrote later:

“That period of 8 years of continuously doing this prepared for the 1960s revolution. I do not believe Montgomery would have been possible nor successful except for the long experience people had about reading about sitting in buses and getting arrested, so that people had become used to hearing this.”

In 1948 Congress debated peacetime conscription. Randolph and Rustin began organizing another March on Washington, which pressured Truman to desegregate the armed forces.

Backlash

In 1953, amidst the backlash of McCarthyism, Rustin was jailed for “sexual perversion” for sleeping with another man, and was fired from FOR after a dozen years of service. His biography describes the profound impact this had on the rest of his life:

“The arrest trailed Rustin for many years afterwards. It severely restricted the public roles he was allowed to assume. Though he fought his way back from the sidelines, he did so at a price. As both the peace and civil rights movements grew dramatically over the next decade, as a philosophy of nonviolence became familiar to millions of Americans, Rustin’s influence was everywhere. Yet he remained always in the background, his figure shadowy and blurred, his importance masked. At any moment, his sexual history might erupt into consciousness. Sometimes it happened through the design of enemies to the causes for which he fought, sometimes through the machinations of personal rivals, sometimes through the nervous anxieties of movement comrades. But underneath it all was the unexamined, because as yet unnamed, homophobia that permeated mid-century American society.”

Birth of the movement

He went to work for the WRL, and when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat and Martin Luther King began leading the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, the WRL funded Rustin to go help. Rustin’s account both humanizes King and shows how he developed through the course of the struggle:

“The fact of the matter is, when I got to Montgomery, Dr. King had very limited notions about how a nonviolent protest should be carried out. He had not been prepared for the job either tactically, strategically, or in his understanding of nonviolence. The glorious thing is that he came to a profoundly deep understanding of nonviolence through the struggle itself, and through reading and discussions which he had in the process of carrying on the protest.”

Rustin brought two decades of experience with mass nonviolent direct action. Along with Randolph, Baker, and Levinson (a lawyer and member of the CP), Rustin built a solidarity network in the north, in unions and on campuses. They argued King should make a permanent activist organization to provide a counterweight to the legal strategy of the NAACP. Out of these discussions the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was born, and then Baker helped launch the Student Non-violence Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

SCLC’s first action, a Prayer Pilgrimage to the Lincoln Memorial, joined Randolph, King, Roy Wilkins (NAACP) and Adam Clayton Powell (Harlem Democrat). Rustin was the main organizer, and the march drew 20,000. The following year Rustin organized a youth rally in Washington—out of the offices of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the union Randolph had organized). These were the first actions that inspired future black leaders, from Eleanor Holmes Norton to Stokely Carmichael. As Carmichael wrote later:

“The first time I saw Bayard Rustin I said ‘that’s what I want to be’. When I saw him I said, ‘that’s it, a black man who’s a socialist, that’s the real answer’. He was like superman. At that moment in time, he appeared to be the revolution, the most revolutionary man.”

Rustin also went to Algeria to help organize against French nuclear testing, mobilizing people to go to the test site—a precursor of the action that launched Greenpeace a generation later. Rustin returned to the US to help Randolph and King plann a march on both Democrat and Republican conventions, to shame both parties for not focusing on civil rights in primaries. This threatened the Democrats and the moderate civil rights groups that lobbied them. So they lashed out at Rustin to stop his influence on King. Powell made a speech claiming the civil rights movement had immoral elements, and threatened to accuse King of having an affair with Rustin. King cancelled the march and dropped Rustin as an advisor—who joined anti-nuclear marches in Europe while CORE launched the Freedom Rides, and debated Malcolm X in Harlem.

March on Washington for jobs and freedom

But Randolph remained a close ally, and in 1963 the two discussed a march on Washington to for the centenary of the emancipation proclamation. It would be called the Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs, putting the black freedom struggle at the heart of the fight for economic justice—moving beyond the limits of civil rights. As Rustin argued:

“Integration in the fields of education, housing, transportation and public accommodation will be of limited extent and duration as long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persists. When a racial disparity in unemployment has been firmly established in the course of a century, the change-over to ‘equal opportunities’ does not wipe out the cumulative handicaps of the negro worker. The dynamic that has motivated negroes to withstand with courage and dignity the intimidation and violence they have endured in their own struggle against racism may now be the catalyst which mobilizes all workers behind demands for a broad and fundamental program of economic justice.”

The Birmingham protests, where police used fire hoses and attack dogs on black youth became the catalyst for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It united the “big 6”: Randolph, NAACP, CORE, SCLC, SNCC, and the National Urban League. This became the big 10 with three religious leaders and United Auto Workers. There was also support from steelworkers, ladies garment workers, packinghouse workers, electrical workers, and labour councils. Rustin was again chosen as the main organizer. Two weeks before the march, the segregationist senator Strom Thurman launched an assault by highlighting the 1953 perversion charges against Rustin, in addition to his history as a war resister and a communist. But this time the civil rights leadership rallied to his defense. The march was historic, and was followed the following year by a mass boycott, under Rustin’s leadership, of the New York City public school system to force it to desegregate.

Debates and divisions

The strategy of the Civil Rights Movement, which Rustin helped develop, was to pressure the Northern state machine and the Democratic party to grant civil rights for the South. The Civil Rights Act was a historic victory, transforming the US and the Democrats, but the same strategy could not work to achieve broader change. As the movement spread to ghetto uprisings and an antiwar movement, Rustin and the civil rights leadership chose Democrats over the movements.

The same uncompromising call for multiracial nonviolence that was his strength became a barrier between him and new movements. He was scathing of black power and refused to support the National Liberation Front in Vietnam. Even after the march, Rustin could not get a position with SCLC. As head of the A Philip Randolph Institute, a labour education organization, he focused on the trade union bureaucracy and the Democrats—calling for a shift “from protest to politics,” subordinating the movement to electoralism. When a riot broke out in Harlem after police killed a black teenager, Rustin and the Big 6 issued a moratorium on all protests until after the election—but SNCC and CORE refused to sign.

The Democrats drove a wedge between the civil rights and anti-war movements and Rustin went along, developing a “Freedom Budget” to argue you could win the war against poverty without ending the war. When King and Rustin were in the White House in on August 6, 1965 for the signing of the Voting Rights Act, SNCC and Muste were outside marking the 20th anniversary of Hiroshima and protesting Johnson’s escalation of the war. But in 1967 King went against the civil rights leadership and spoke out against the war, connecting militarism abroad with poverty and racism at home. King also planned a Poor People’s march on Washington and went to support sanitation workers on strike. As Rustin’s biographer wrote, “the pupil had surpassed the teacher,” and it was then that King was killed.

Rustin was never again in the thick of the struggle—and ended his life supporting right-wing NGOs—but he did support civil rights for gays and lesbians by lobbying NY city council to add sexual orientation to the human rights code, arguing that “today, the barometer of where one is on human rights is no longer the black, it’s the gay community.”

Despite the faults in the last chapter of his life, Rustin was central to the black freedom struggle—and in a difficult time, in the shadow of Stalinism and before Stonewall. We need to take the best lessons of his life, building mass movements linking struggles against war, economic inequality and all forms of oppression.

For a 10 minute documentary of Bayard Rustin, go here. For the full-length documentary Brother outsider, watch below.

Section: