Features

You are here

20 years since Gustafsen Lake

August 18, 2015

Twenty years ago, Indigenous Sundancers stood their ground against the RCMP’s largest operation in Canada’s history, under an NDP government. This took place at Ts’Peten, or Gustafsen Lake, in central BC, in Secwepemec territory.

In 1989 the Sundancers, under spiritual leader Percy Rosette, began holding their traditional ceremonies at Ts’Peten, a site that was surrounded by land used by non-indigenous rancher Lyle James. All had agreed to the use of the site as long as no permanent barriers were constructed. In 1995, when the Sundancers put up a fence to keep out Lyle’s cattle from defecating on the site, James asked the Sundancers to leave.

They explained they could not leave until the ceremonial cycle was finished. After night time harassment from local cowboys, two Indigenous members of the RCMP were put in place to “keep the peace” for the 20-30 Sundancers, including men, women and children.

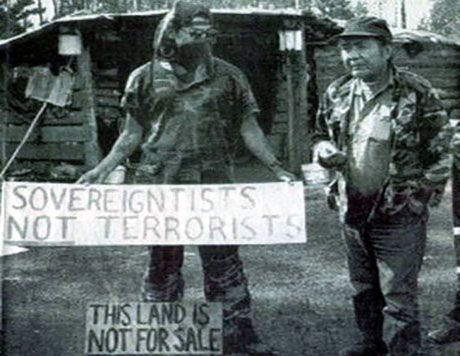

Two spokespersons for the Sundancers, Wolverine (aka Jones William Ignace) and Splitting the Sky (aka John Hill) asserted the right of the Sundancers to occupy the site until the ceremonies were over, and that the site was part of unceded Shuswap territory. Tensions then arose with some locals about claims to the land and there were reports of gunfire.

The RCMP intervened with 400 officers. AFN Grand Chief Ovide Mercredi tried to bring the Sundancers, or Ts’Peten Defenders, out of the site. After Rosette issued a media release on August 24, 1995, to “seek a peaceful resolution to a crisis which has been going on for 139 years”, the RCMP cut off communications to the camp and set up their own media centre.

The state and the NDP

Thus began a classic smear campaign, with police characterizing the Ts’Peten Defenders as “terrorists”, “criminals” and “thugs.” A video of RCMP officers discussing smear tactics against the Defenders was submitted as evidence in court, and today can be viewed on Youtube. To top it all off, local media were not allowed to enter the site, which meant the only interpretation of what was happening was coming from the RCMP.

Worst of all was that this “standoff,” which began August 18, took place while the NDP was in power in BC. The Attorney General Ujjal Dosanj made the shocking statement “Where’s the other side of the story? There is only one side of the story. There is no other side.” In other words, the Defenders had no right to speak about the site or about indigenous rights more broadly. And when the RCMP alleged they had been shot at (a charge later shown to be a fabrication, but consistent with the smear campaign), Dosanj used this as a pretext to have the Department of National Defense send in armoured personnel carriers and other equipment including land mines that were set around the camp.

Two Sundancers hit a land mine on September 11, when they tried to drive out of the camp to get water. The RCMP shot at and wounded them while they attempted to flee, thought luckily not lethally.

Throughout this period, Sundancers trickled out of the site, trusting in their Indigenous negotiators. The crisis came to an end on September 17 when the last Defenders left the site, on assurances from the RCMP that there would be no arrests. But, consistent with historic betrayals by the state, the police arrested 18 people, including a sentence of four years in prison to James Pitawanakwat—who fled to the US after his release one year after his incarceration, fearing for his life. The US refused to grant the extradition request made by the Canadian government. Wolverine was forced to spend five years in jail following his arrest.

While there was not universal support for the Defenders from all Indigenous people, especially among the political leadership, the conflict was admired by most as an assertion of indigenous rights. Unfortunately, there was not much in the way of widespread solidarity from non-indigenous sources, a situation that was not helped by the NDP government’s negative characterization of the situation. This was the same government that established treaty tables in 1991, but only enabled a handful of “agreements.”

Afterwards

“Gustafsen Lake” is part of the “red thread” of resistance by Indigenous peoples and horrendous state repression. The position of the NDP is consistent with other betrayals when the NDP has formed government or even while in opposition, such as when Mulcair called on Chief Theresa Spence to call off her hunger strike, precisely when Idle No More was taking off in popularity. The situation in Gustafsen Lake might have been resolved with more fairness, and no arrests, had there been more widespread and visible solidarity from the public.

Despite demands from the Ts’Peten Defenders, the government has never agreed to a public inquiry to examine the excessive use of force by the police. This is consistent with the Tory refusal to conduct a public inquiry into the tragedy of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Another Sundance leader, John “Splitting the Sky” Boncore, told the Globe & Mail, “At Gustafsen, we raised the bar. In the long run, if there is a disturbance at the grassroots level and people who are not content with what is going on start to assemble, the government now fears another Gustafsen uprising.” BC Premier at the time, Michael Harcourt, claimed that the stand-off was no more than “a criminal matter”, with no effect on government policy. To see how incorrect this statement was, look no further than Harper’s intended use of Bill C51, the Anti-Terrorism Act, to wipe out indigenous opposition to new pipelines carrying bitumen and other dangerous forms of oil or other toxic substances.

Thanks to Idle No More and other indigenous sovereignty activity, we are seeing the kind of alliances and mass action needed to support indigenous self-determination and respect for indigenous traditions and spirituality.

Section: