Features

You are here

Missing and murdered Aboriginal women: when will there be justice?

April 15, 2014

For many, the tragedy of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls first became prominent with the media coverage of Robert Pickton’s trial. Pickton was convicted in 2007 for the murder of six women in his slaughter house in BC’s Lower Mainland, east of Vancouver. He was also charged in the murders of another twenty women, and prosecutors say he confessed to murdering 49 women, many of whom were Aboriginal.

The delay in his trial, and many concerns cited during the trial, raised questions about the lack of seriousness with which police respond to calls regarding violence against women, particularly poor women, particularly if they are Aboriginal. And if they are sex workers, they are beyond the pale.

In BC, public awareness was also growing with the recognition of the Highway of Tears, a stretch of highway in northern BC from Prince George to Prince Rupert, where female hitchhikers were killed at a stunning rate. Between 1969 and 2011 it has been estimated that there were to 43 victims, and over half were Aboriginal women or girls.

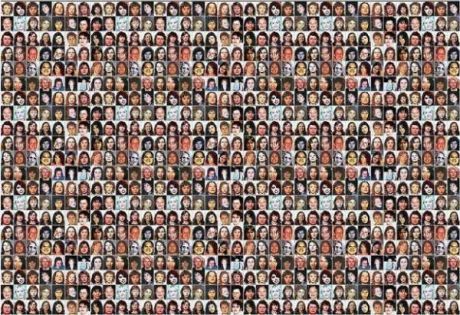

The Native Women’s Association of Canada conducted extensive research and education for its Sisters in Spirit campaign, beginning in 2005. Predictably, the Harper government cut funding for NWAC and the group has had to significantly reduce its work in this area. An independent researcher, Maryanne Pearce, has been able to continue the data collection and analysis, at least for now. Her latest estimate is that there are more than 824 missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls where there are no arrests, let alone convictions. If this were happening to the non-Indigenous population in Canada at the same rate there would be 18,000 missing or murdered women and girls.

Root causes

The extensive number of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls, and the low “solve rate” raises many issues, all of which revolve around the question of “why?” This question is best answered by looking at the impact of colonization, poverty, racism, sexism, and the role of the state.

The Highway of Tears exemplifies many of these root causes. Women and girls hitchhike because of poverty, either they lack their own cars or they can’t afford the infrequent Greyhound bus. Poverty for Indigenous women on both their traditional territories and in urban settings also causes some women to turn to sex work, and street-level sex work in particular creates enormous vulnerability.

Another issue is lack of police follow up, which can only be attributed to racism and sexism. A study by Human Rights Watch documents "not only how indigenous women and girls are under-protected by the police but also how some have been the objects of outright police abuse...young girls pepper-sprayed and Tasered; a 12-year-old girl attacked by a police dog; a 17-year-old punched repeatedly by an officer who had been called to help her; women strip-searched by male officers; and women injured due to excessive force used during arrest. Human Rights Watch heard disturbing allegations of rape and sexual assault by RCMP officers, including from a woman who described how in July 2012 police officers took her outside of town, raped her, and threatened to kill her if she told anyone."

The lack of government action at every level has been mind-boggling. After years of community demands, the BC government established an inquiry led by judge Wally Oppal. Aside from major problems of insufficient involvement of indigenous community representatives, the impact of the inquiry was minimal. Even the recommendations Oppal made were not effectively implemented; e.g. a Highway of Tears co-ordinator position had its funding removed within a few years of its inception.

The response by the Harper government has been even worse, using the rhetoric of action to dismiss an inquiry. "I don’t think you have to be a rocket scientist, and I don’t think you need a national inquiry, to find out what the problem is," Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development minister Bernard Valcourt told the National Post. "This is happening because, we know, of the legacy of decades of policies towards First Nations that have resulted into what we have today. What is the way out? The way out is not to study anymore. The way out is to take action.” Not that the Tories are about to take any action either, aside from actions to further the colonization of indigenous communities, to make way for tar sands development and the extraction of other profitable resources for private corporations.

These are common threats facing Indigenous people across the Americas: recently a Honduran human rights activist visited Six Nations to speak about "the common struggles that all Indigenous people of the Americas face including high rates of murders, violence, and disappearances as well as struggles with displacement and pipelines."

Action and solidarity

Indigenous communities have long been calling attention to both the disproportionate rate of murdered and missing Aboriginal women, and the disproportionately low police “solve rate” for these cases. As early as 1991 there have been annual marches in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (considered Canada’s “poorest postal code area.”). Indigenous protesters and their allies have since held these marches in many cities across the country to commemorate the loss of Aboriginal women and to demand justice.

There are annual Sisters in Spirit Vigils held every Valentine’s Day in numerous cities across Canada and Quebec. Calls for a national inquiry have been made for years through the Native Women’s Association of Canada, the Assembly of First Nations and individual First Nations. Activists from one First Nation, the Tyendinaga, have taken repeated direct actions including railway and road blockades, to call attention to the issue.

First Nations have not been alone in their calls for justice, the bare minimum of which would be a national inquiry. Support for an inquiry has come from social justice movements, political organizations, faith organizations and trade unions. These include everything from the United Nations and the federal NDP and Liberal parties to provincial and territorial premiers, Kairos and individual faith organizations, and Human Rights Watch. Of particular weight is the support from trade unions, not only through the Canadian Labour Congress but also through individual unions such as Unifor and the Steelworkers.

NWAC has issued a Community Resource Guide: What Can I Do to Help the Families of Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women and Girls? The Guide “is a plain-language publication that has been designed to assist educators, health and service providers and other allies with the necessary information and tools to work in a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner with families who have lost a loved one.”

May 11-12 the Nishnawbe Aski Nation is organizing a 24-hour Sacred Gathering of of Drums on Parliament Hill to honour missing and murdered Aboriginal women and to call for a national inquiry.

If you like this article, register for Marxism 2014: Resisting a System in Crisis, a weekend long conference in Toronto June 14-15. Sessions include "Environmental racism and climate justice", "Today's resistance to the genocide of Indigenous People", and "Socialism and indigenous sovereignty."

Section: