Features

You are here

Lest we forget: Canada, WWI and revolution

November 8, 2013

Having wasted $30 million celebrating a rewritten history of the war of 1812, Harper is getting ready to roll out a propaganda campaign about World War One. But we should remember why WWI was fought, and how it was resisted.

WWI: a war for Empire

In December 1914, six months into WWI, Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden announced “there has not been, there will not be, compulsion or conscription. Freely and voluntarily the manhood of Canada stands ready to fight beyond the seas in this just quarrel for the Empire and its liberties.”

Borden was right about one thing: WWI was a “quarrel for the Empire.” Driven by imperial competition, Western powers that had carved up the world went to war with each other to see who would dominate. Canada went to war to defend the British Empire and strengthen its own power, sending 67,000 Canadians to their deaths.

But this was not a war to defend liberties. In 1914 Canada was in the midst of running its concentration camps—the residential schools—as part of its genocide against First Nations. Homosexuality and abortion were illegal, women were not even considered “persons” under the law, and the vote was denied to indigenous people, immigrants of Asian origin, women, people with disabilities, and men without property. Any progress we’ve made been a result of people fighting for their own liberation, against the Canadian state, not Canada joining an imperial war.

Remembrance Day: a product of revolution

As a result of seeing the reality of war, participation in WWI became less free and voluntary, as soldiers began resisting—from an unofficial truce declared on Christmas, 1914, to mutinies in the French army in 1917, to revolutions in Russia in 1917 and Germany in 1918—giving us Remembrance Day.

Borden went against his word and imposed conscription, and when there was a rebellion against it in Quebec he sent in Anglophone soldiers to fire on the crowds. The Canadian state then joined a dozen other countries in sending soldiers to crush the Russian Revolution. But this only increased anti-war and revolutionary sentiment—documented by the historian Ben Isitt in his book From Victoria to Vladivostok.

As Joseph Naylor, president of the BC Federation of Labour and leader of the Vancouver Island coal miners said, “is it not high time that the workers of the Western world take action similar to that of the Russian Bolsheviki and dispose of their masters as those brave Russians are now doing?”

War and resistance at home

Sending troops to Russian coincided with an attack on the labour movement—including the killing of socialist and trade union activist Ginger Goodwin, which sparked a general strike in Vancouver on August 2, 1918, the first in Canadian history.

As Issit writes, “the government’s actions of autumn 1918 were motivated by domestic class relations and by events in Russia and responses within the Canadian working class. Bolshevism would be wiped out by banning radical parties and newspapers, jailing dissident workers, and invading soviet Russia from the Siberian front. However, inadvertently, the Borden government strengthened ties between Canadian workers and Russian Bolsheviks. The two-pronged strategy of domestic repression and foreign intervention appeared to confirm a commonality of interests, drawing parallels between conditions of revolutionary Russia and wartime Canada and strengthening the appeal of the Russian model as a vehicle for social change. Canadian incarnations of Bolshevism, rather than being crushed, would come to play an important role in the unraveling of Canada’s Siberian expedition.”

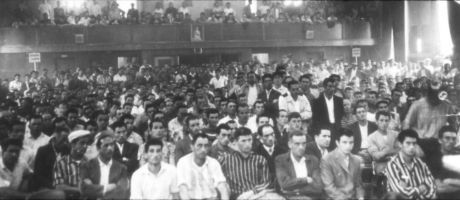

In December 1918 there was a mutiny of Quebec soldiers in Victoria refusing to be sent to Russia: “The French-Canadian conscripts who arrived in Victoria were mustered from the districts around Quebec City and Montreal, which had experienced rioting in opposition to the Military Services Act; in the British Columbia capital, they encountered a robust socialist movement that identified with the aims of the Russian Revolution and launched a determined campaign to prevent their deployment to Siberia. In street-corner meetings and in packed auditoriums, working-class leaders of the Socailist Party of Canada and Federated Labour Party provided a vocal critique that transformed latent discontent among the troops into collective resistance. At this junction of social forces—the converging interests of working-class Quebecois and BC socialists—a violent standoff erupted in Victoria.”

This was part of broader resistance that paved the way for the Winnipeg general strike of 1919: “Unrest mounted among labor and farm organizations. The labour councils in Canada’s four largest cities—Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto and Montreal—declared against the Siberia expedition, as did the labour federations of BC and Alberta and union locals of AFL-affiliated machinists and railway workers. A mass meeting in Winnipeg’s Walker Theatre—described as the penultimate event to the Winnipeg General Strike—called for the immediate withdrawal of the troops.”

Borden ultimately crushed the general strike, and counter-revolution and isolation crushed the Russian revolution. But remembering Canada during WWI is a reminder of why wars are fought, how they are resisted, and how this can pave the way for a new world without capitalism and war.

Section: