Arts

You are here

Poems and propaganda

November 8, 2013

I am willing to bet that the only poem many Canadians can quote is “In Flanders Fields”. Canadian Lieutenant Colonel John McCrea wrote it in 1915 following the Second Battle of Ypres, where German forces used chemical weapons for the first time. Once a year at Remembrance Day it is trotted out and drilled into the heads of successive generations of children. To refresh your memory:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The story goes that McCrea was dissatisfied with the poem and tossed it away, but fellow officers rescued it. Pity. What starts out as an invocation of the horrors of war is undercut by the crassly jingoistic final stanza.

In his wonderful analysis of the literature emerging from the war, The Great War and Modern Memory, historian Paul Fussell slams the propagandistic turn of the final verse: “Words like vicious and stupid would not seem to go too far….”

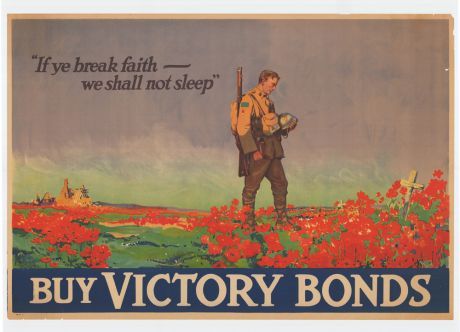

The British press was entirely censored and controlled during the war, with hardly a negative word about the war appearing. McCrea’s poem was published in Punch magazine and became an immediate propaganda hit. It was used in recruiting posters and campaign to sell war bonds.

At the time of publication there was a push for a negotiated settlement of the war, and Fussell notes that “In Flanders Fields” was prominently employed to muster popular opinion against such negotiations, helping prolong the slaughter for three more years.

At home it was prominently used in the 1917 election campaign by Tory Robert Borden, and to rally English Canadians against the strong opposition to the war in Quebec. McCrea, a supporter of Empire, was delighted; he wrote: “I hope I stabbed a (French) Canadian with my vote.”

WWI resulted in many fine works of literature–novels like Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, memoirs like Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That, and poetry by the likes of Wilfred Owen, Edmund Blundon and Sigfried Sassoon–but “In Flanders Fields” is not among them.

But even as doggerel it pales beside the honest, ironic and often ribald poems and songs created by anonymous men in the trenches. In most, the miserable conditions and filth of trench warfare take centre stage:

Far, Far from Ypres I Long to Be

Sing me to sleep where bullets fall,

Let me forget the war and all;

Damp is my dugout, cold are my feet,

Nothing but bully and biscuits to eat.

Over the sandbags, helmets you’ll find

Corpses ahead and corpses behind.

Far, far from Ypres I long to be,

Where German snipers can’t get me.

Damp is my dugout, cold are my feet,

Waiting for the whiz-bangs to send me to sleep.

Sing me to sleep in some old shed,

The rats all running around my head,

Stretched out upon my waterproof,

Dodging the raindrops through the roof,

Dreaming of home and nights in the West,

Somebody’s oversized boots on my chest.

Other poems are parodies of popular songs, like this crude one that turns the tables on a jingoistic recruiting song, “Come My Lad and Be a Soldier”:

I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier

I don’t want to be a soldier,

I don’t want to go to war.

I’d rather stay at home

Around the streets to roam,

And live on the earnings of a high-born whore.

I don’t want a bayonet up my arse-hole,

I don’t want my bollocks shot away.

I’d rather be in England,

Merry, merry England,

And fornicate my bleeding life away.

In most of these rank and file ditties the villain is seldom the German soldier; more often the enemy is the officer or sergeant. My favourite is an ode to a particularly snotty British General named Cameron Shute:

That Shit Shute

The General inspecting the trenches

Exclaimed with a horrified shout,

‘I refuse to command a Division

Which leaves its excreta about.’

But nobody took any notice,

No one was prepared to refute,

That the presence of shit was congenial

Compared to the presence of Shute.

And certain responsible critics

Made haste to reply to his words,

Observing that his staff advisers

Consisted entirely of turds.

For shit may be shot at odd corners,

And paper supplied there to suit,

But a shit would be shot without mourners

If somebody shot that shit Shute.

Any of these rhymes does more to capture the real experience of World War I than “In Flanders Fields”. Small wonder none of them ended up on recruiting posters. But I know which one I’ll be thinking of come Remembrance Day.

Section: