Arts

You are here

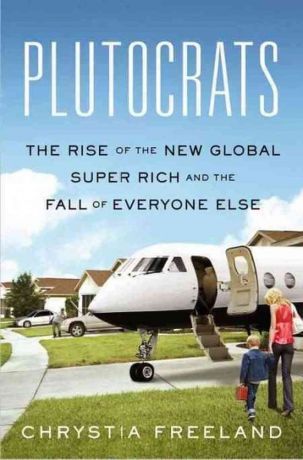

Anger and uncertainty about the 1%

February 10, 2013

Plutocrats shows a clear influence from the Occupy movement and laments the rise of such intense income inequality around the world between the 1% and the 99%. However, Freeland posits few, if any, ideas to reverse the growth of inequality. Instead Plutocrats is focused mostly on describing the demographics of the 1% and how they got there.

This doesn’t mean that the book is not useful for socialists and activists of the 99%. In many ways it is. Plutocrats makes some of the arguments that Marxists have been insisting on for years.

Most forcefully, she emphasizes that the Plutocratic class “are becoming a trans-global community of peers who have more in common with one another than their countrymen back home.” This is important to emphasize because just as today’s super-rich are an international class with an interest in maximizing profit, the working class of the world too has a common interest in usurping the power and privilege of the 1% whether they maintain primary residence in New York or Hong Kong, Moscow or Mumbai. While the Plutocrats of the world are international, their metaphorical gravediggers are too.

She also provides statistical evidence that contradicts the argument that workers in America benefit from some kind of labour aristocratic position compared to workers in the less-developed countries. She notes that “the big winners from Apple’s innovation were the 6,101 engineers and other professional workers in the US who made more than $525 million. That’s more than double what the nonprofessionals in the US made, and significantly more than the total earnings of all of Apple’s foreign employees.”

Freeland continuously emphasizes the importance of class struggle and the fight for political and economic reforms in making life bearable for the 99%. She refers to Lenin and the Bolsheviks throughout the book (usually as a good idea gone too far) and recognizes that “the victorious communists were influential far beyond their own borders—America’s New Deal and western Europe’s generous social welfare systems were created partly in response to the red threat. Better to compromise with the 99 percent than to risk being overthrown by them.”

Freeland’s work also emphasizes other points that the activists of the 99% would be happy to hear. She identifies the way in which market liberalization, deregulation and privatization have created more billionaires and widened the gap between the highest income earners and everyone else, noting: “Russia’s oligarchs have done so well for themselves that inequality today is higher than it was under the tsars.” She also points out the effect that the plutocrats have on passing legislation and even quotes numerous plutocrats stating their disdain for the lower-classes and acknowledging that they would have to pay the price for society’s “progress.”

No alternative

But Plutocrats is a frustrating book to read. Freeland, who spent years as a journalist for the Financial Times, sees few alternatives and presents almost none in this book. Very early on the book she states “today, the evidence that capitalism works is clear, and not only in the wreckage of the communist experience.” Because she takes for granted that capitalism and some form of market system is the only way the world can operate, the book’s main debate is how free should markets be. Consequently, Plutocrats resides in a strange space where it chronicles in great detail the problems with today’s capitalist system and its recurrent crises, while simultaneously defending it tooth and nail.

Much of the book is spent describing the 1% and 0.1% as self-made billionaires, who are innovative, mathematical geniuses who have the creative vision and talent to take advantage of changing situations. This becomes a bit too nauseating when you realize what her definition of self-made is (consider that she describes former Prime Minister Paul Martin as a “self-made multimillionaire”) and after about the millionth reference to the “knowledge economy”—while failing to acknowledge that the “creative genius” of the Steve Jobses of the world would be nothing without the thousands of Chinese and Filipino hands that actually build his iPods.

Anger and uncertainty

So Plutocrats is a book that very much expresses the times we live in: a time that is simultaneously mired in capitalist crisis, but without the kind of working class fightback needed to make the rich pay and provide a clear alternative.

Plutocrats expresses both this anger at the super-rich for their profit at the expense of the rest of us, but it is also unsure about what can be done about it. Freeland attacks the “philanthro-capitalists” for their charitable solutions to inequality, but she also identifies aspiring billionaires as the social force motivating protests in Egypt and Russia. Clear ways forward are hard to come by, but Freeland seems to be making the case that the bankers and lack-of-regulation have put us in this mess in what could otherwise be a healthy capitalism. She suggests that by regulating and mitigating the effects of the profit-motive, a more equal and just capitalism can be obtained.

Read this book, but read it critically. Read it knowing what famous plutocrat Andrew Carnegie knew, that “capitalism…required employers to drive the hardest possible bargain with their workers.” This conflict, between the workers producing the wealth and the Carnegies taking it, provides the framework for looking at the rise of the plutocrats and the people who can collectively stop them.

Section:

Topics: