Arts

You are here

War of 1812: myth and reality

August 23, 2012

We know that Tory cabinet minister Peter MacKay skipped math class in school, since his figures on G20 spending never added up. Now we know he skipped history as well: at a recent event at the French embassy celebrating Bastille Day, Clement thanked his hosts for fighting side by side with the British to defeat the Americans in the War of 1812.

We know the Harper Tories are spending at least $28 million to commemorate the war that “defined” the nation. It is a pity they didn’t put a few dollars towards cabinet briefing notes. Then MacKay might have known that Britain was in the midst of war against Napoleon, and that France was allied with the US in 1812.

MacKay might have read any of the plethora of books on the subject published recently. Just in time to cash in on the anniversary, veteran left nationalist James Laxer has produced Tecumseh & Brock: the War of 1812. Laxer argues: “The fires of war were forging an identity in Upper Canada, whose elements would be evident for many decades to come. Indeed, the contemporary political culture of Ontario has its roots in the war.”

It would be absurd to pretend the war had no impact on the “identity” of Canada, but Laxer like most Canadian commentators take the questionable step of declaring Britain (for “Canada” did not exist) the victor in the war. It is just as logical to argue that the US identity was also defined by the political and military struggles of 1812-14, but Laxer dismisses that idea as American propaganda and “self-evidently absurd.” To admit it would put in jeopardy the cherished notion that “we” beat “them.”

Happily, there is a far better book available that begins with the premise that in North America, in 1812, there was no “us” and “them.” Alan Taylor’s The Civil War of 1812 is a masterful work of historical research that argues that there was little or no difference between settlers on either side of the northern border. Internal divisions and struggles on either side of that border were just as important to the outcome as military battles.

The US was split by partisan battles between Republicans and Federalists that make today’s Republican vs. Democratic bickering look like a schoolyard spat. Federalists, who held the majority in the New England states and in the New York territory along the border, absolutely opposed the war, refused to serve in the militias, and did what they could to undermine those who did. Pro-war Republicans representing the southern slave states, western frontier and growing cities bursting with new immigrants (especially pro-republican Irish) held the majority in congress and elected James Madison president. These “War Hawks” were also fanatically anti-tax and opposed to any real power for the federal government. Wars and armies cost money, yet right up to the eve of war they refused to raise taxes to form an army and especially to build a navy. As a result they depended on militias and suffered economically from a British blockade of the eastern coast.

Laxer and most Canadian nationalists latch onto War Hawk rhetoric about “manifest destiny” the idea that absorbing Canada through military or other means was their god-given right. Leave it to Taylor, a better historian with no nationalist axe to grind, to point out that the fate of the Canadian colonies was debated in congress, and plans to absorb them into the Union were easily voted down. Southerners worried that admitting more anti-slave territories would upset the delicate balance, and business interests thought it best to use them as bargaining chips to get better access to markets controlled by British naval power.

Canada would probably have remained a separate state even if the war had been decisively lost.

On the Upper Canada side (what is now Ontario), settlers were overwhelmingly drawn from the US, lured by the promise of 200-acre farmsteads virtually free, with no taxation. The builders of empire called these “Late Loyalists”, to differentiate them from the United Empire Loyalists who had fought along side the British in the Revolutionary war.

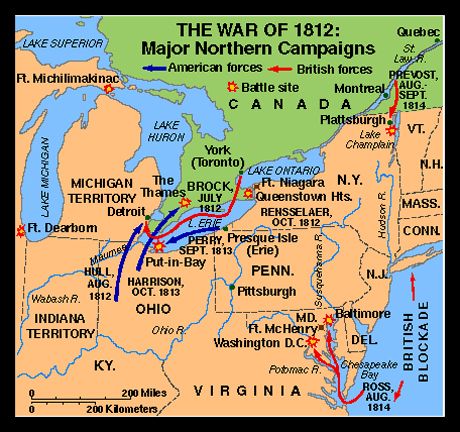

Late Loyalists were asked to take an oath supporting the king, but colonial administrators had no illusions—they were just as likely to support invading American forces as British defenders. In fact many settlers would support neither side, being made up of pacifist religious sects like Mennonites, Shakers, Dunkers and others. Practical people, the settlers waited to see which way the wind was blowing before coming down on one side or the other. Since the first six months of the war saw stunning defeats to the US—forts at Michilimackinac and Detroit were surrendered virtually without a fight; the Battle of Queenston Heights was determined more by American ineptitude than the heroism of General Brock—public support swung behind the British.

Much is made of the fact that the burning of York and the looting perpetrated by invading Americans turned the population against the republic in the south. But Taylor shows that poorly provisioned troops on both sides looted the countryside to feed themselves. Poorly prepared and led troops along the US Niagara frontier also looted farms and towns on their own side. A significant battle ensued when mostly Federalist citizens of Buffalo turned out to battle Republican looters threatening their town and businesses. Laxer’s work is devoid of such fascinating insights: a tantalizing mention that some inhabitants of York joined in looting the town is not explored.

Even the role of First Nations in the war reveals the character of a civil war. The best part of Laxer’s otherwise plodding book is the section on Tecumseh, and the “Creek War” between US southern militias and First Nations traditionalists inspired by the great Shawnee war chief. The Americans excelled in manipulating divisions between and among nations, and Native fighters were on both sides.

Laxer works mightily to create the idea that the British, and especially Brock, were more respectful of First Nations allies than the Americans. He even floats the argument that had Brock lived the British might have honoured the promise to create a Native buffer state in the Ohio/Indiana territory. Not bloody likely: this was the first demand the British dropped at the bargaining table that produced the Treaty of Ghent. Both sides exploited and betrayed their Native “allies”; any differences were more style than substance.

If you are going to read anything on 1812, make it Taylor’s brilliant and readable history. It exposes a war resembling a comic opera one moment, and marked by fratricidal atrocities the next. He shows that both the US and Canada are transformed more by the economic and political struggles leading up to, during and following the war, than by the actual battles. Not only is it a great read, it is a powerful antidote to Harper’s 1812 propaganda campaign.

Section:

- Log in to post comments