Columns

You are here

Anti-racist feminism

April 1, 2012

The women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, commonly referred to as the ‘second wave,’ developed in the context of mass movements of protest, including the black civil rights movement and opposition to the war on Vietnam. These movements were young, diverse and often fragmented, but generated considerable influence in theory and practice.

The development of a tradition of anti-racist feminism, in both social movement organizing and theoretical scholarship, is one of the most important, but also often neglected, contributions of this period.

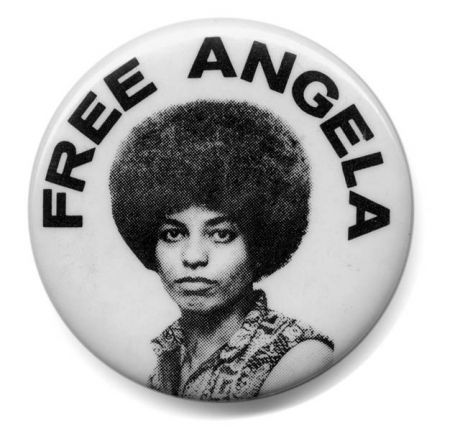

Anti-racist feminists in the US were and continue to be among the most active. Angela Davis is one of the most influential to advance this approach, notably marked by the 1981 publication of Women, Race and Class.

Davis is Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness Department, and former director of Feminist Studies, at the University of California, Santa Cruz. But even this position is a mark of her activism. In 1969, her involvement with the Communist Party and association with the Black Panthers led then California Governor Ronald Reagan to have her removed from teaching at any university in the state.

Davis was put on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted” list, arrested, and faced the death penalty at the time of her arrest. She was tried in 1972 after sixteen months in a California prison.

Soledad

Her arrest was based on suspected involvement in the case of the Soledad Brothers.

Three African American prisoners, including George Jackson, were charged with the 1970 murder of a white prison guard at California’s Soledad Prison. Angela Davis—along with those such as Noam Chomsky, Pete Seeger, Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda—participated in the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee to advocate for a fair trial. Jackson’s brother, Jonathan, was involved in holding up a courtroom and taking hostages in an attempt to secure his brother’s freedom. Davis was charged with involvement in this event.

Following a mass campaign, Davis was acquitted on all charges. This was a significant victory for civil and women’s rights, freedom of speech, and prisoner solidarity.

Continued

Angela Davis has continued to be part of the US and global movements for prisoner rights and social justice. In 2011, she travelled to Palestine with a delegation of women of colour feminists, who wrote a public declaration in support of the BDS campaign (bdsmovement.net).

As a public intellectual, Davis has advanced studies that focus on the intersection of gender, race and class.

While taking the starting point of an emphasis on social reproduction, many contributions in anti-racist feminism explain how capitalism, in concrete historical conditions, shapes working class families in different ways.

Margaret Simons, for example, in a 1979 article in Feminist Studies, titled “Racism and Feminism: A Schism in the Sisterhood,” challenged a classic feminist analogy that compared sexism to slavery. A tendency to over-generalize from white, middle class women’s experience opened the door to liberal feminism. These perspectives:

“…often deemphasize the differences in women’s situations in an effort to point out the shared experiences of sexism…. Perhaps most importantly, in the context of a dialogue between minority and white feminists, the notion of an absolute patriarchy can obscure the reality, all too familiar to minority women, that some white women have historically had access to power which they have at times wielded against both minority men and women.”

Another important contribution is Leith Mullings’ On Our Own Terms, published in 1997. As an anthropologist grounding her work in Engels’ Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Mullings investigates the role of African American women, and men, in the production of US capitalism.

Plantation slavery, apartheid-like Jim Crow laws in the South, and racist employment practices, meant that racism, sexism and class exploitation shaped the nature of working class families in specific ways. As Mullings notes:

“In most U.S. cities, the constraints on the ability of African American men to earn a ‘family wage’ forced African American married women into the labor market in greater proportions than Euro-American wives. By 1880, 50 per cent of African American women were in the work force, compared to 15 per cent of Euro-American women. While the majority of working women of both races were unmarried, a significantly higher proportion of African American wives worked.”

Mullings traces her work to the debates in US politics dating back to the civil rights movement, noting the formative impact of Angela Davis. Mullings also identifies the successful battles to establish ethnic, women’s, labour and black studies programs in the universities, and considers the expansion of scholarship in these fields to be products of those efforts. The capacity of ‘writing African women into history’ would not have been possible without the social movements of previous decades, and continues to be under threat from neoliberal attacks.

Marginalization

The effort to silence Davis in the 1960s and ‘70s is reflective of a long history of marginalization of women of colour. An explicit aim of anti-racist feminism has been to challenge the threat of invisibility, to make the voices of black and Third World women central to movements for social change.

The socialist and anti-imperialist struggles have greatly benefited, and continue to grow in strength and influence, from these contributions.

Section:

Topics:

- Log in to post comments